The early starts are gradually coming back again, or else as the year grows, the road tightens its alluring grip on us. This morning I was up at 5.30am, and out before dawn. I made a start with lamp lit at 6.30, and traversed the lightening lanes to Walkden, en route for Kingsway End, 8am, to meet Tom. Dawn came dully and disinterestedly on the road to Barton. At Chorlton, a big, red sun was rising, reflecting its deep colour in the windows. It gradually rose, until it hung, a shimmering, huge, watery-looking orb in the eastward heavens. It was a fine sight undoubtedly, and seemed to me to prophesy rain in plenty. I had not long to wait before the familiar figure on the familiar, dirty Chater Lea hove in sight. We had ambitious designs for the day, for we intended to get into the Trent Valley, beyond Newcastle under Lyme. Alas for plans and intentions!

After he had criticised my dirty shoes, and I his dirty bike, we got on the road again. By some strange outburst of energy, I had cleaned my machine, and Tom, suffering from the same momentary complaint, had removed the last few months of mud from his shoes, hence the criticism. Usually, we are both negligent on this point, and rollick week after week in an ever-growing coat of mud and dust, the collection of many shires and hundreds of miles. But anyway, we got on the road, and soon left Cheadle behind, speeding along deserted Wilmslow road. The hills on our left were clear-cut against the white sky, and the big, watery sun was disappearing behind a gloomy cloud.

Handforth was put behind us, then Wilmslow, and Alderley Village, a modern, residential place. Strictly speaking, this is not Alderley at all, but Chorley. The advent of the railway probably had something to do with it, for the station was called Alderley Edge, from the wooded eminence at the foot of which it stands. So completely has the new name ‘taken’, that the old name is rarely heard, and even some of the residents know nothing of ‘Chorley’. We walked up the hill, then half a mile further along, came to Nether Alderley, the real Alderley.

On the main road are just a timber and brick abandoned mill, and a little general store with two or three cottages beside it, making a quaint, picturesque scene, whilst through the trees can just be seen the tower of the church. A little lane led us to the ancient church, which, with its stone covered roof and its Sanctus belfry, is a venerable building. A curious projection on the outside, like a transept with steps running up to it, is the Stanley Pew. From the inside it looks like an opera box. We had a walk inside the church, and had a chat with the caretaker. Amongst other interesting things, we learned that all the books in this private pew – which is kept locked – have been signed by Queen Victoria.

The pleasant road led us through Monk’s Heath and by Redesmere, which stands in the grounds of Capesthorne Hall, to Siddington. Now we had started to potter, and began to feel disinclined to crash through the Potteries, so yielding to the temptations of the lanes, we turned right at Siddington. Our main concern became to keep clear of main roads, and this resolution held all day. The winding byways led us for many a pleasant mile to Dicklow Cop. We stopped once for a light lunch and to gather some palm, then came a little wooded valley. For about a mile we kept to the right bank, to Swettenham, a village with an old, red brick church, the tower of which is entirely covered in ivy. Dropping downhill, we ran across the swollen, rain-flushed River Dane, and up through the grounds of Davenport Hall. A watersplash lay in our way, about 5” deep and about 15 feet long, but it looked worse than it was. We were finding mud very nicely, despite Tom’s avowal to keep out of it today.

Crossing the Congleton-Holmes Chapel road, we rode by Brereton Heath, and through a dull, marshy district to Brereton Green, on the main road. Here stands one of England’s famous coaching inns, the Bear’s Paw. It is a wonderful example of black and white timbering, and produces such an old-world atmosphere that I should not have been surprised to find an old stage coach with its four horses and big, red faced driver pulling up here for a brief spell. Now a straight muddy bylane took us through many fields towards a display of stumpy chimneys and huge works, heralding the Salt County. We were much puzzled by numerous red and white signposts without wording in the hedges, but could not decide their use. This district is usually one to be avoided by cyclists as a dull, monotonous, spoiled countryside. We found it unavoidable in our case, and decided to get through it quickly. Middlewich is a salt town, as is Nantwich and Northwich, the ‘Wytch’ or, as is now spelt ‘Witch’, meaning salt, therefore Northwich is North Salt Town, Middlewich middle salt town and Nantwich, lower salt town, nant being the Celtic word for hollow, valley, or low place; the word ‘nant’ will also be found in common use in Wales, the Cumraeg tongue there giving it as ‘glen’ or ‘vale.

I have often thought that our English place names give a world of evidence of locality, industry and position, such as the folks in town do not dream. It forms a fascinating study also, being of great educative value as well as interesting. There are very few places whose names cannot be traced back to some dim age or ancient language. Three common examples are ‘ton’, ‘ford’ and ‘caster’, words which frequently occur at the end of a name. ‘Ton’, a corruption of the Saxon ‘tun’ meaning fortified place, is perhaps the most common. Thus, with ‘ford’, a river crossing, and where ‘ford’ occurs, one can safely say that the place stands by some waterway. It has no reference to a certain notorious make of motor-car! ‘Caster’ is of distinct Roman origin, and is often corrupted into ‘chester’, such as Manchester, Chester, and Ribchester etc. Of course, these are only the simplest and commonest forms.

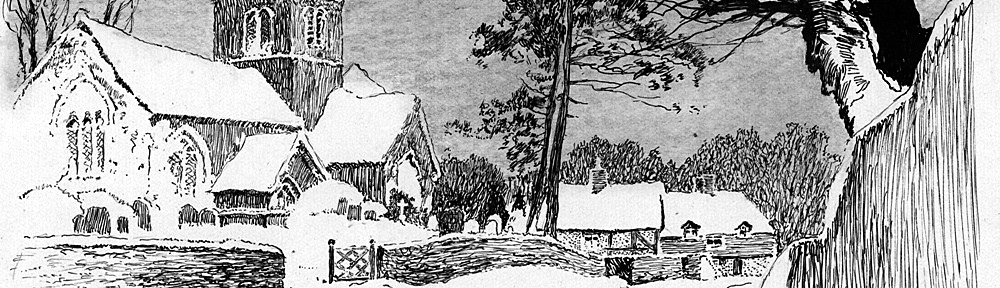

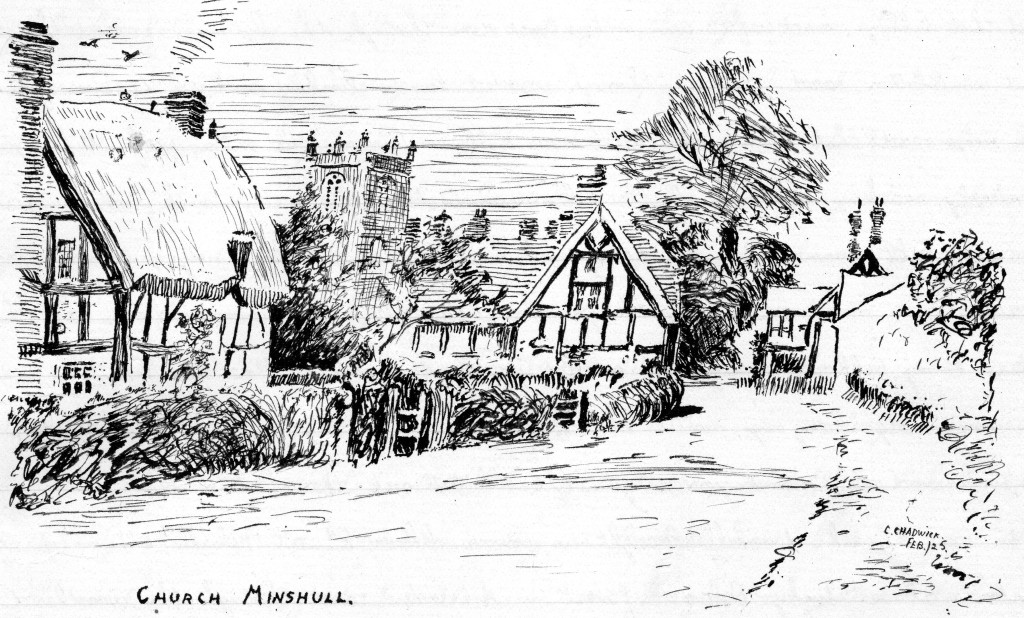

But I am wandering off the ride again. The day, contrary to expectations, had become warm and sunny, and perfect for cycling. We soon had enough of the salt district, and were glad to get away from it. After many more miles of winding lanes, we joined the Nantwich road at Minshull Vernon, and a little further on turned towards Church Minshull.

A sharp drop brought us over the River Weaver, which is not polluted and very pretty here, and immediately we reached the typically rural village above mentioned. The one fault in the place is the church; it is an ugly red-brick building, a relic of the hideous building of the 19th century, and does not at all blend with the picturesque ‘wattle and daub’ houses that line the road. ‘Ye Olde Badger’ provided our lunch, and here we discovered the reason for the coloured, (red and white) wordless signposts. They are used in the hunting season to warn the horse-riders that barbed wire lines the hedges hereabouts. The colour has no meaning. It is so simple that I wonder we did not think of it ourselves.

After an hour we came out and joined the Wettonhall road, crossing an agricultural district, and eventually reaching the grounds of Calveley Hall, then running by the wall to Wardle, and so along the Nantwich-Tarporley road to Calveley and Highwayside. Rushing over the canal and the River Gowy, we climbed into Bunbury, a neat little place with an ancient church standing on a knoll. We made a bee-line for the church, and entered. There must be a children’s service or something held here on Sunday afternoon, for as we went in we were followed by a host of youngsters. We did not stay long, just taking a hasty glance at some old stone coffins and their quaint lids, and some finely painted windows in memory of the Calveley family. I should have liked to examine the old edifice, but we were afraid lest the parson should come and persuade us to stay! So we got out before he saw us.

Turning down a narrow lane we drew a blank and had to retrace our steps, but we found the right way, and headed for Spurstow. These roads traverse wonderful surroundings, and the typical Cheshire homesteads abound in this district. Reaching Spurstow, we traversed two dull miles of the Tarporley-Whitchurch road, then turned right, dropping downhill towards Bulkeley. The brown, swelling Peckforton Hills rose before us, a glorious picture. We stopped a moment to drink in the magical scenery, and to marvel at our means of travel, the little mounts that had brought us right across this beautiful county. The sky was deep blue, with white fleecy clouds spread-eagled across the blue, and the sun was warm and bright. At Bulkeley we joined the Beeston-Bickerton road, deserting it later for a sandy channel which led into the hills. We were soon walking, the gradient being too much. By a shady wood it started to climb an even steeper gradient, into the Peckforton Gap. Longfellow wrote:

‘If thou art worn and hard beset

With sorrows, that thou would’st forget;

If thou would’st read a lesson, that will keep

Thy heart from fainting and thy soul from sleep;

Go to the woods and hills! – no tears

Dim the sweet look that nature wears’.

and he must have had something like this in mind when he wrote those lines.

On the summit we left the bikes, and climbed over the rock and gorse to the highest point, sitting down on a huge boulder, and enjoying the views at leisure. Eastwards, the sun smiled on the rich, rolling plains with its winding brown lanes and rural hamlets, and bounded by the Cheshire Highlands. The smoke-pall in those hills to the southeast denote the Potteries. In the west, the land swelled downwards to level country, in the midst of which the silvery ribbon of the flooded River Dee made a winding, flashing border course. Then the ground heaved up into a lumpy mass of mountains, range upon range, height upon height, rugged and rounded, ‘Wild Wales’. The black chaos of earth culminated in the peaks that dominate the fair Vale of Clwyd, and above all, rose the bulky sides of Moel Famau. Northwards, the Mersey Estuary could be seen, and the hills of Frodsham and Helsby, which from here appear as mole-hills, whilst southwards, the lower moorlands reached into misty distance.

We returned to the road, and soon came to Burwardsley, with a side view of Beeston. A long drop down, and an easy run brought us to Tattenhall, where we turned for Huxley. We soon reached that village, and after an enchanting run through the bylanes, crossed the Chester-Tarporley road at Clotton, and plunged through wooded lanes, climbing a little to Quarrybank, on that glorious ridge road that rounds the Kelsborrow Hills. Passing the entrance of Willington Hall, we climbed steeply, reaching the head of the hills, and taking a rutty track, which gave advantageous views all round. For many miles we rode along the ridge, then stopped to watch the sunset. It seemed as though the Welsh mountains were on fire, the black, rugged contour being silhouetted against a blazing background. The western sky was deep dyed, gradually changing, until the hills were in shady outline, the heavens were a delicate pink and blue, and gradually twilight blotted out the distant views.

A rush downhill brought us across Chester road at Kelsall, then up again, until we stood above dusky Delamere Forest. A cinder road through the woodland glade led us to Delamere station, then Hatchmere, and the winding downhill miles through Norley and Crowton to Mrs Wade’s for tea. We were hungry, and the place was packed with the Liverpool Century RC, but after a long wait, we managed to shove in with five Manchester DA chaps.

It was 7pm when we restarted, and lamps had to be lit. We made good progress to Acton Bridge, and through the darksome lanes via Little Leigh and Comberbach. A rush was made through Great Budworth to avoid the church crowd, then came the bumpy journey to High Legh and Broomedge, where was the parting of the ways. After arranging for next week, each went his own way. Mine lay over Warburton Bridge and across dismal Chat Moss to the streets of Atherton, and Squires Brow home, at 10pm, after a truly delightful, spring-like day. 115 miles

Pingback: Intent upon Trent is not a Town | Charlie Chadwick