Ambition is the forerunner of trouble. The We.R.7. CC are ambitious, and therefore, in the wake of the We.R.7, trouble is often churned up. And not only for the ‘We Are Seven’. Each one of us cherishes, apart from cycling, some personal ambition, which now and then infects the rest, when trouble with a capital ‘T’ usually turns up. When Tom gets going with his camera he turns pictures out that are beautiful, and pictures never intended to be beautiful, or to be shown round (by his victim). I know, for a certain unposed camera study which I own a not unnatural likeness to, has found its way into an exhibition and half the ‘grub shops’ we haunt. And then there is that Fred fellow, who, had he been gently stifled at birth, would have saved several people from misery. His one ambition in life seems to be to torture his victim to death by means of repartee and practical jokes, and so subtle is he over it that all but the sufferer takes it as a joke! They each of them have their ambition in one way or another, and I have mine. Thereon hangs a story.

It was a particularly hot Easter Sunday when five particularly hot ‘We are Seveners’, after clearing the entire stock of a catering house, found themselves in the Pass of Llanberis. I was one of the five so as I had read much of the certain wild little lake in the lap of the cliffs of Crib Goch, I said “Wot abaht it?”, ‘it’ being a scramble up to the lake. There must have been a superabundance of energy amongst them that afternoon, for they agreed, and we dumped the bikes and, like an attacking army, spread ourselves all over the screes, each taking the ‘easiest’ way. Now I am concerned with my own little exploit. My great ambition next to cycling was rock-climbing, (it’s a lesser ambition now), and I decided that rock-climbing it should be. When I was seventeen and before, I possessed the normal lust for ‘penny dreadfuls’, and always the biggest ‘dreadful’ was that in which the hero hung by his finger nails to a towering precipice, or got wandering in underground passages where death lurked at every step. The higher the precipice, or the lower the tunnel, the bigger the thrill. I have previously explained the subterranean side, so now for the other.

Reading about it was not enough, for a cousin of mine who was more daring, and myself, went on climbing expeditions to various quarries, and many were the tight corners we got into. We holidayed every year together, and it was our boast that we could climb the cliffs at Bray (Ireland) and Douglas Head in the Isle of Man, in their most difficult points. I was only about eight years old when he saved me from at least a serious injury on Bray Head, and so I always looked on him as the leader. (Poor fellow, he is married now, I was the best Man). For a time cycling made me forget climbing, but when I saw the granite giants of Wales my old longing to emulate a fly on the wall returned, so I guessed that here was my chance.

On the unprotected slopes the hot sun beat mercilessly, and it was real toil on either slippery grass or amongst little boulders. When at length we reached the hollow we found another endless scree leading up to another recess which was Cwm Glas. A little to the left, however, a stream came cascading down jagged little precipices and monstrous rocks, and, by taking the course of it, I calculated on a more interesting and direct ascent. The rest preferred the screes, with the exception of Billy. As luck would have it I had chanced on a good ‘staircase’ climb, though the rocks were not ideal, neither was the shower bath which fell to my lot more than once when I had to recourse to the waterway. Once I dislodged a boulder that would weigh somewhere near half a ton, and sent it flying down (inadvertently), rebounding and splintering as it crashed from cliff to cliff with a force and noise that was stunning, and bringing in its train a thousand others. A spectacular sight but dangerous when others are in its way, and a little awkward for the climber when it goes without warning. By the time I reached Cwm Glas the others had been and turned back with the exception of Fred, who, like me, had the fever on him, and motioned me to come along higher. But a moment in Cwm Glas!

Picture two little lakes – one with an island in it, the other very tiny; behind them a wild scree sweeping steeply upwards to the base of a huge semicircle of rocks which rose in a jagged line into the blue sky; that is Snowdon’s wild northern arm, Crib Goch (Red Ridge). Follow the crescent round, see how the crags break into furrows and bulge outwardly, until the end comes in one great bastion of toothed rock, which is called Clogwyn-y-Person, or the cliff of the Parson. The Parson’s nose is an overhanging abutment that is all splinters and seems ready to fall away from the main mass. Turn about and look down the screes and across the chasm to the mountains beyond. The immense cliffs we saw from the Pass are dwarfed; behind them is ranged peak above peak, crag above crag, precipice above precipice. Even this in our own little Wales makes one catch his breath and realise the smallness of man and the vastness of the world.

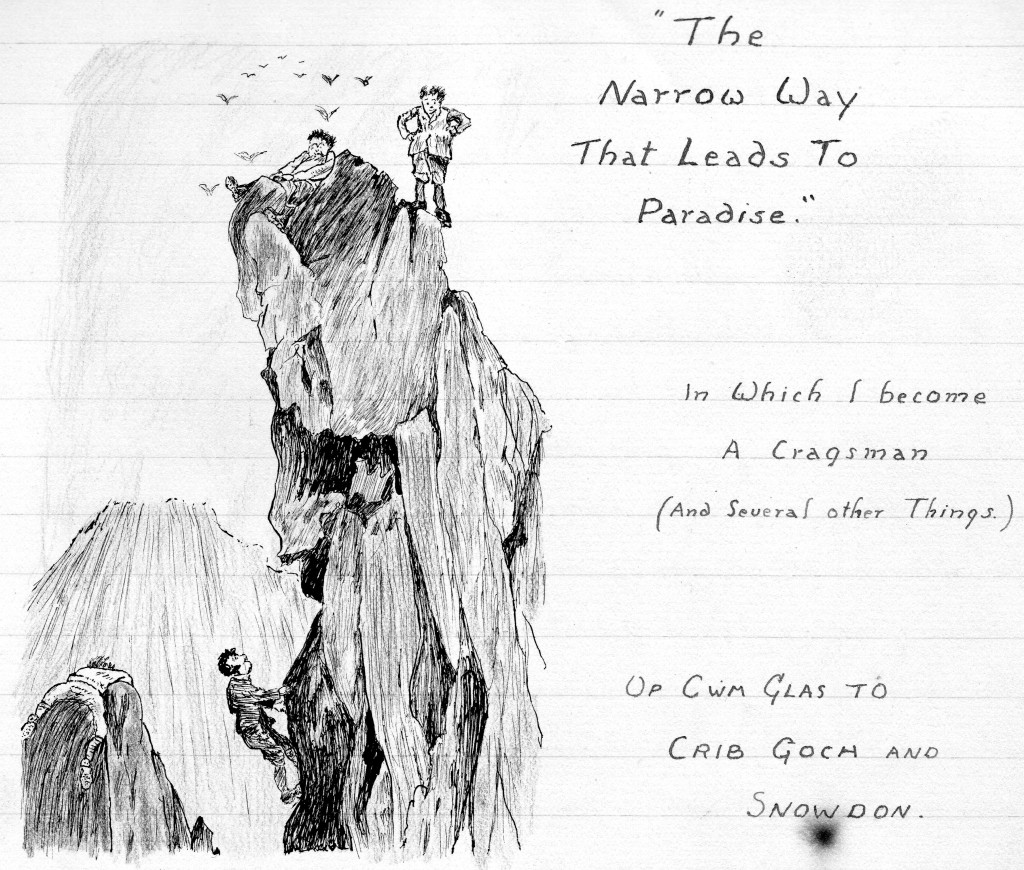

I made a move after Fred, but after a lot of slab-climbing found a deep crevice between his route and mine, so I started to climb the rock-face, hoping to reach the summit quickly that way. What a novice I was, trying to scale cliffs that experts avoid! The rock was rotten; it lay in a slantwise stratification, and was at first full of holds, none of which were secure; but I had let my enthusiasm run away with me, and climbed on and on blissfully. The holds became less frequent and more shaky, the rock becoming perpendicular, so that looking down between my feet I could see Llyn Glas like a little pond. Then an outward bulge put an effective bar to progress, and though I scrutinised the rock I saw no possibility of climbing another foot. How much harder it is to get down than to climb up!

I tried to descend but found I daren’t move, so I hung on a bit and surveyed the wild cliffs on each side and watched the shadows creep across the solitudes and stared down through a hundred feet of nothingness between me and the lakeside slabs. But my hands were tiring. I tried to leave my perch again, lowering my feet towards a ledge, taking the weight on my arms. Knowing the condition of the rock I might have guessed what would happen. The knob of rock in my left hand broke, the other slipped, I said aloud “Now I’m done for!”, and slid downwards. How I kept upright I don’t know, but I grabbed at one ledge then at another, gaining speed, until my foot caught a jutting piece, and before I could go backwards I frantically grabbed at another and stuck. I stuck a while, too, gathering my wits together, wondering what I should have felt had I gone backwards and cleared a hundred feet at once, and measuring the distance I had slipped, which I estimated at about twelve feet. Without mishap I covered the rest of the descent to some smooth, shelving slabs, which I tried to cross in a sitting posture, started to slide, and got a sickening sensation before I could scotch myself, and, reaching firm ground, breathed a sigh of relief. Damages: rubbed skin off my wrist, torn shorts [known as knickers in those days!], and barked shins; I had had a marvellous escape.

The shadows had entirely covered Cwm Glas when I crossed it and wormed my way down the long screes to the boggy hollow, towards those ever so tiny crawling things below – the motors on the road. Looking back I saw the cliffs I had essayed to climb. Why, I had been attempting suicide, for above the point I had reached they hung like a great canopy. From the boggy hollow the ‘crawling things’ resolved themselves into traffic, and at length I joined the party. We waited a long time for Fred, who, when he reached us waxed enthusiastic over the climb. He had found a break in the cliffs, and reached the summit of Crib Goch (3,023 ft), telling us of the wonderful views from that point. And I, seeing a new way up Snowdon, resolved that Cwm Glas had not done with me

The Second Attempt

As I have explained earlier in ‘This Freedom’, my real reason for making a dash from Devon was to climb Snowdon with my uncle. Now my uncle is my superior by at least 15 years, and is quite an orthodox person. He is a motor-cyclist of the easy-going-I-am-out-to-see-the-scenery type, had the orthodox hatred (I won’t say fear) of rain, likes long rambles on a path, and likes climbing mountains – on a path. I am orthodox too, though I don’t care a damn for the weather, like long rambles mostly off the path, and like mountains, though I don’t care for a path up them. I claim, (modestly enough) that I possess a bit of the ‘old Adam’. So when I had been in Cwm Glas at Easter, I figured that that was my way up Snowdon. The guide books warn people to climb Snowdon by the defined routes only; one going so far as to issue a solemn forecast of trouble for the novice who tries to reach the summit via Cwm Glas and Crib Goch, painting horrible pictures of past accidents and incidents, and telling how strong men cross the ‘Crazy Pinnacles’ on their hands and knees in fear and trembling. My own particular bit of ‘old Adam’ therefore rose, and if I had possessed any doubt about the wisdom or otherwise of the ascent, it was thereupon banished. It would be via Crib Goch or none! Uncle was ignorant of all this, so I had hopes of dragging him up too, and when the two London cyclists asked if they might come along I jumped at it. So it came about that we were four.

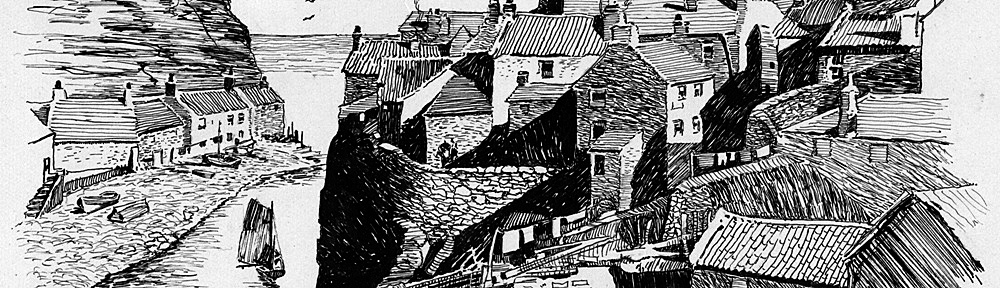

For many people the weather that day would have put the lid on our plans, but not so us, though uncle was not too keen when he saw the ceaseless rain and the heavy mists which cloaked every height around. We got Mrs Jones to pack us a great load of sandwiches in two (converted) rucksacks, and bought some chocolate and fruit, and thus armed started towards the Pass. I did not think it was so far. After a good hour walking we came to Nant Peris at the foot of the Pass, so being hungry we got a pot of tea at a pub and made the first inroads in our rucksacks. By then it would be about 1pm. Then another long walk brought us to our starting point just below Pont-y-Cromlech, midway up the Pass of Llanberis.

The rain came down in torrents and an upward glance revealed the plastic mists engulfing all but the lower screes. The impression I gained at that moment was tremendous, and I think I realised the significance of what we were tackling. “Reach Snowdon through that!” cried my uncle, “never; do you know the way?” “Of course”, I said, lying glibly. By the time we had climbed 200 feet of screes, uncle revolted. “I’m not going up another inch, its madness”, he said, and urged us to go back with him or let him go, which we did, reluctantly enough. Afterwards I was glad for he hasn’t got the perspective for this kind of ‘stunt’. We settled down to a hot, wet scramble over bog and rock and stream until we reached the first hollow which was very lonely and wild. Below, everything was wrapped in mist, above, very near to us, the curling grey tongues rolled, and from somewhere amid them came a waterfall, the cascading stream of Easter, bounding down in a wide ribbon to this boggy hollow. That was our way. We scrambled on, the ascent becoming steeper and more awkward; our capes had long since proved too great an encumbrance and had come off; we were rain-saturated and being drenched again and again by the torrent up which we had to squirm. We each chose his own way though we kept in sight, for one would often dislodge a boulder and send it crashing down, down into the mist below, and following it by sound, hear it break to fragments amid deafening echoes. But, bound in his task, each of us were immensely happy because we liked the delicate traverse of some guileless-looking ledge, or the careful use of hands and knees and feet – and head in some treacherous gully ascent. And when we came to where a second hollow lay shrouded about us, hemmed by cliffs of which we could only see the base, I knew we had won the first round – we had reached Cwm Glas.

Then we made our way to Llyn Glas. I took my bearings from a point where I had stood last Easter – that is to say that I guessed at my bearings, for the Cwm was gloomy and the mists hung round so that I could only guess where the breach in the cliffs was. If I only guessed a few yards wrong we should find ourselves climbing some of the most dangerous cliffs on Snowdon. And well did I know the difficulty of returning – the slip last Easter proved that. It was with a confidant face but a very doubtful heart that I pointed the direction, and my friends, in the belief that I knew Snowdon, climbed on merrily.

A sense of awe and wonder crept up me, as I stood there, and felt the conflicting emotions of confidence and doubt change to growing fear of the possible conclusion to this hair-brained ‘stunt’, and to get my mind away from these thoughts I became active again and pushed after my comrades. I am not romancing, but stating plain facts, though they may seem coloured enough to one who lives his life in the streets of our towns; they are really jade in comparison. Picture Cwm Glas, the wildest hollow in Wales, fill it with a cauldron of grey mist, make yourself hear the buffeting roar of a gale above, see in your mind’s eye, a cascading thread of water here and there coming wildly down a jumble of huge blocks of granite, then add three tiny beings amongst this wilderness of granite, and still you would be far from visualising Cwm Glas as it was that afternoon.

But all the fearfulness left me when I felt the tingling excitement of the climb, and all doubt was cast behind me. It was hard, exciting, ticklish work on those crags, but still we kept mounting upwards, slowly and certainly until I knew I had guessed right. We were in the breach, the only way (except for an equipped and expert party) from Cwm Glas to Crib Goch. Jack and I topped the crags simultaneously, then waited a long time for Bill who came up, cheerful head first, when we had shouted ourselves hoarse. After that we climbed a kind of pebbly beach which stretched up into the mist for a long way. Just when I thought we had reached the summit there suddenly loomed in front an array of jagged cliffs. I got a shock. Were we to be stopped after all by unclimbable rocks? If so – well we could never hope to get down to Cwm Glas. To our surprise we found these pinnacles comparatively easy, but on emerging from shelter we exposed ourselves to the gale which tore across the summit with shrieking velocity, and we had the utmost difficulty in keeping upright.

What a journey we had then, over the ‘Crazy Pinnacles’, a fantastic array of rock-needles, onto the ridge of Crib Goch, where, on each side a precipice shelved away for a full thousand feet into the mist, and where the driving rain cut into our faces, and the wind tried to tear us from our insecure perches. In one place we had to run like blazes across a little exposed opening else the tugging wind would have bowled us over the edge. But we made progress, and at length were able to leave the ridge, and struck the railway line. A few yards brought us to the summit of Snowdon, and beating a tattoo on the door of the ramshackle wooden hut, we were admitted, a trio of drenched and shivering, but triumphant ‘mountaineers’.

We quaffed cups and cups of hot tea, finished all our ‘snap’, and solved a crossword puzzle for the innkeepers lad. The room was so snug and cozy, and the conditions outside so terrible, we hung back for over an hour. Then putting our capes on, we literally took a header into it. Snowdon is 3,560 feet above sea level, but there is a huge cairn on its utmost summit, so we must needs bring ourselves another ten feet higher by clambering on it and standing there for a moment, bent to the wind, surveying the sea of mist and rain around us. That was all we saw, mist and rain.

Then we started our return journey down the railway track, running as fast as we could to get warm. No trains were running, the conditions being far too dangerous. We made amazing progress for a time, but when the edge of Cwm Clogwyn was reached the wind came in wild fury and blew Jack clean over. To escape further buffeting we lay down flat, then made a run for it between gusts, running and throwing ourselves down until Clogwyn station was reached. After a breather we made another dash as fast as ever we could, for at this point the line runs on the edge of the 1,000 foot Clogwyn precipice. Though we kept on the right side of the track we could feel the wind tugging at us, and expected another blast at any moment. We heard it coming with a whistling noise, flattened ourselves out, and clung to Mother Earth. As it passed it swept the mist away for a moment, and looking down into Cwm Clogwyn we saw the tiny strip of road deep below in the Pass of Llanberis. Another rush landed us safely in a cutting, and after that we found the shelter of a low ridge and were able to walk down in comparative comfort, leaving the line for the footpath. We got below the mist, gaining a good view of Llanberis lake (Llyn Padarn) ‘ere the woods were reached. So we arrived back in Llanberis to a worried landlady and uncle, chilled and thoroughly wet, but bursting to tell our story.

It was a venture, perhaps a mad venture under the wildest conditions. As a search for view it was a washout, but as a search for excitement it proved an El Dorado, and none of us would have missed it for worlds. And there was a sequel. While we were relating our tale to an interested party, Mrs Jones, at the mention of Cwm Glas told us a story of which most will remember, for it was given wide publicity.

Two climbers from London went into Cwm Glas last Autumn (1925), to try to climb Crib Goch. They were roped up, equipped for the game, and were experienced as cragsmen. They started from the slabs above Llyn Glas, climbing directly beneath the Pinnacles, but when about 200 feet up one of them found the rock to be in bad condition and his progress was barred. In trying to descend he slipped, and both fell down to the slabs, one being killed outright and the other breaking a leg and receiving other injuries. There he lay unable to move for three days and nights, calling at intervals, but not until the fourth day was he heard, and rescued in an almost dying condition.

It struck me that the cliffs I tried to scale last Easter were the same that had caused this tragedy, and the way I had slipped was the same. Needless to say my pet ascent of Snowdon lost a little of prestige with me! But climbing is a great game, bringing one near to the beauties of the earth, and taking one to those great rock-bound places where ‘Nature’s heart beats strong amid the hills’.