Post: By the time you have finished this visit to Speedwell Caverns, you will know all there is to know about lead mining. Lead was first mined in Derbyshire by the Romans, and a lot of money has been made doing so, and some have lost their shirts. And Tom’s knee is a lot better.

Sunday, September 20 Edale and Speedwell Cavern

Arrangements had been made with Tom to meet him at Kingsway End, 8am, and ‘Blackberry Joe’ and Ben decided to come as well. Joe is turning out with us regularly now, and has altered his ways immensely. He is not the ‘blind and stop’ cyclist that he was, he is a far more even rider, his gear has come down 8” (to 66”), and he can ride at a good pace all day and never tire. But he can potter too, now, though not ‘really’; he still, however, prefers roads of a better calibre to ‘river beds’ or sewers, but that will wear off if he continues with us. Like most real cyclists, he cheers up, and sings loudest when the weather is filthiest.

At 4.30am I was prowling about the house cat-like. You see I awoke at 4.30 and got up because I feared that if I stopped in bed any longer, I would ‘go off’ again and be late. So I chose the safest way. At 6.15 Joe came stealthily in, and then stealthily we both slipped away. Yes, for once, Blackberry Joe was stealthy. The last time he called at 6.15am, all the house became aware of his presence and some grumbling ensued, and when we told him to keep quiet he let his bike fall over – that’s Joe! Ben was not waiting at the arranged place, we allotted him an extra ten minutes, but he came not, so off we went. No need is there, to recite the 17 miles of Not Much to the Cheadle end of Kingsway, at which point we arrived simultaneously to Tom, and which point we left after the usual criticism of bikes and apparel. Joe’s shoes shone like a mirror; Tom’s and mine were what he called a disgrace, (what is a disgrace?), so as we toddled through Cheadle on the Edgeley-Stockport road, we hatched a plot ‘gainst Joseph’s shoes, and made our most urgent business the downfall of that ultra-reflective gloss. I thought he’d learned sense by now!

The sky had been a glorious colour-scheme of red shades; now was an unfathomable blue with a cold watery sun blinking at us. “We shall have rain”, chanted Tom. At those words we ought to have made all possible haste to get home. We did hurry, but it was in the wrong direction, for we were not in the least getting nervy over it. In Wigan, I hear, they let it. I suppose we would too. The Stockport-Hazel Grove road gave us a shaking up on the setts, but at the latter place we were delighted to see that a beautiful tarmac surface was being laid. Buxton road is tarmac on one side, so the drag up to Disley was smooth at least.

After that came some pretty woodlands, then a ‘shelf’ ride, with a grand outlook across New Mills to the wild region of High Peak. At Whaley Bridge we turned towards Chapel-en-le-Frith, and were fanned along by the cold breeze, uphill to that celebrated village (or town), but on the road beyond, fanning was of little use to get us up to the top, ‘shanks’ was easier. We had a choice of two roads here, the Sparrowpit-Winnats road to Castleton or the main road over Rushup Edge. As we had never been on the main road, and as the Sparrowpit road has often been used, we chose the main road. It was too early yet for the traffic, so we had the road to ourselves.

It was ride a bit, walk a lot through Slackhall, but the scenery was excellent and magnificent views were opening out. Near the summit we stopped awhile to take in the scenes behind us, which included the pastoral park and finely laid-out buildings of Ford Hall, the enclosing mountains beneath which runs the railway through Cowburn Tunnel, huge green-brown clods of earth rising towards barren Kinder Scout to a height of over 2,000 ft, the valley in which runs the Chapel-en-le-Frith-Hayfield road, with Chapel at the near end and Chinley situated in a recess about the centre between Eccles Pike and Chinley Churn. Right across the valley at the summit of a spur of Kinder was the line of Andrew Rocks, with brown, steep roads climbing to their base. The visibility was excellent this morning.

The road flung us ultimately on to wild moors, 1,405 ft high, and ran on a slight down-grade beneath the ridge of Rushup Edge. On the other hand we got good views of Sparrowpit road and the heights beyond. It was a freewheel mostly, down to the Edale turn, up which road we tried to rush, but it was too much and our rush up Rushup Edge (pun!) petered out into another walk. Then we found ourselves level between two ridges, and all at once the ground seemed to drop away beneath us. We looked down into the Vale of Edale.

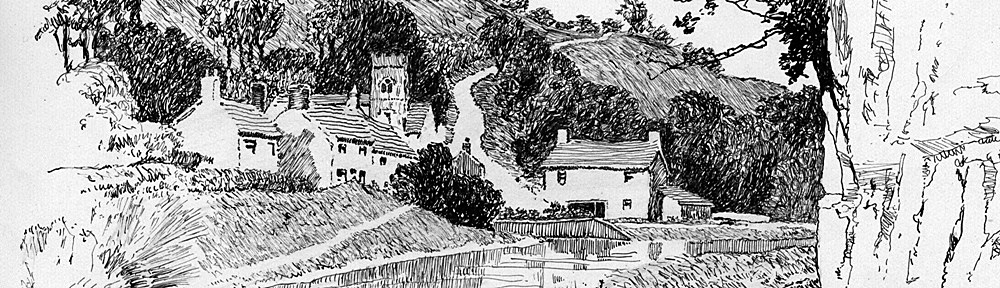

Edale is a magnificent, fertile valley, a cul de sac, surrounded by great huge moors, wild and forbidding on a stormy winter day, a vast mass of colour under a sunny autumn sky. To us it was a picture of sunshine and shadow, for now the transparent blue sky had changed, and the high wind sent dark clouds hurrying across. Sunshine and clouds chased each other across these swelling ridges, and they appeared first in gold shades, then dark, almost black. Below us the white road leapt downwards with hurrying gradient and reckless bends to the tiny roofs that are known as Barber Booth; the same white road continuing along the valley, skirting Edale village. The valley was green, the fields and trees and wooded patches being laid out just as is, as Tom said, a Welsh valley. I could picture the Glyn Valley here – or was it the Rheidol Valley, or the Vale of Clwyd? Then down we plunged, bounding towards the rapidly growing buildings.

A corner, a quick pull-up, the one calliper brake (front) straining, the front wheel’s sliding ‘crunch’, the bank, over which is a steep, heathery slope, suddenly jumping alarmingly close to the skidding wheel, a sharp intake of breath as I simultaneously balance carefully to the left and turn the wheel almost imperceptibly, my left foot ready to avert the skid by a dig at the flying road beneath. Ah! the road suddenly straightens out before me and with a sigh of relief (the calliper taking a stronger grip), I proceed more cautiously round the next bend and decide to descend no more hills like this one on a freewheel. What would have happened if the strain had proved too much for the brake cable? Only a fortnight ago I broke two brakes in this way.

Then Barber Booth resolved itself into a village street, and we followed a winding lane beneath the shadows of Mam Tor and Lose Hill, with the River Noe and the railway in close companionship for many beautiful miles, until passing by some prettily set stone cottages, we come to Hope and the main Castleton road. After a pow-wow, we faced a high wind, crawling along the Hope Valley to Castleton. We had changed our plans and decided, if we could, to visit one of the three big Lions or more, Peak Cavern, Speedwell Cavern, or the Blue John Mine. Behind the main road, near the church, we discovered a good lunch place, and repaired thither to line the inner man, before carrying out our voyage of exploration which was to be done on foot.

When we started, the weather was doing its best to rain, and Joe, with commendable forethought, brought his cape along with him. We made our way through the side streets to a footpath running by a river in a ravine, the while the crags on each side became higher and more sheer. The river came out of the ground, quite suddenly boiling up about 50 yards from the entrance to the Peak Cavern which we were approaching. Turning a bend, we came quite suddenly on a huge, bulging mass of rock which assumes the appearance of a huge, depressed arch which forms the mouth of Peak Cavern. Overhead, on the left, on the verge of a precipitous crag which overhangs the ravine, was the ivy-clad, ruined keep of Peveril Castle.

A vast canopy of rock, which forms the entrance to the first cavern, is 42 feet high, 120 ft wide and more than 300 ft deep. Here, in the cavern were several poles with arms on them, situate on giant ‘steps’, and reaching into the darkness. We were much puzzled over them, and I later discovered that they were the remains of a pack-thread or twine works, which has had its home in this sheltered cavern for hundreds of years. Then our eye caught a notice board which plainly read ‘Closed on Sundays’. Peveril Castle, we discovered, is also closed on Sundays, so after seeing what we could from the wrong side of the railings, we returned down the ravine and took a footpath which brought us out on the moors, heading towards that impressive gorge, the Winnats.

A heavy rainstorm came on, so we all got under Joe’s cape, and continued thus until we reached the road at the foot of the Winnats, just near the little building and shop which is the entrance to Speedwell Cavern. Luckily, our arrival made up a party of ten, including four girls (or young women) and three old ladies, so we paid our ‘bob’s’ and passed through the turnstile into the hut which stands over this, the one and only way in. We were full of anticipation, for many times have we heard of the wonders of these limestone caves.

The guide lit a brilliant acetylene torch and distributed candles amongst us, then we descended a very long flight of rough steps which led into the bowels of the earth. There are 106 steps, and it was impatiently slow work waiting for the old ladies coming. At length we reached a platform over a dark waterway where a long narrow boat was moored; into this we stepped, finding some amusement watching the trembling old ladies hesitatingly enter. At length all were seated, we three being behind, and with a push, the boat was started, and the guide got the boat under way, sending it along by pushing the roof with his hands, and at intervals placing lighted candles on the wall by means of clay. We noticed that he always placed one just near or where another had been. He must know the place inside out. The passage is 9 feet high and never over 7 feet wide, so that there was just room for the boat to pass; the water in the passage is about three feet deep, and so low was the roof that we had to keep our heads down if we wished to avoid a nasty crack. All the while the guide was chanting sonorously such as guides do, in ‘book fashion’. This canal is 750 yards long to the bottomless pit, so that including the return, we had nearly a mile of boating. Drill marks on the roof and sides became more numerous as we got deeper, for the rock was harder and therefore needed more drilling prior to blasting.

The tunnel was driven 150 to 200 years ago, and took 6 to 7 years to excavate. The expense incurred was very great – £14,000 I think. This of course is not comparable to present day monetary value, but when it is known that nearer the deeper end, drilling became so expensive that the cost was around about a guinea an inch for drilling alone, it will be realised that a large outfit would be required to make the mine pay. It was worked entirely for lead, for though fluorspar was found in rich veins, there was not sufficient quantity to make it a paying proposition. The mine proved a dead failure, for only £3,000 worth of lead was ever found. Progress, proving very slow, the owners of the mine sent down to Cornwall for experienced tin-miners, but they were used to softer rock and were an utter failure; the Derbyshire men could work faster.

Here and there, small recesses marked the places where the miners huddled to escape the flying splinters of rock during blasting, and at intervals were the scooped-out ‘pockets’, where pure lead had been mined. In one place we passed a narrow, tortuous cave, where a vein of lead had been followed out. It illustrates the awkward, dangerous positions in which those early miners had to work. Across the roof could be seen thin veins of lead, and great white and blue tinged masses of the beautiful topazine fluor, or fluorspar. As all the lead and fluorspar veins run from east to west, the mine was driven due south, so that the veins would be crossed.

About 200 yards on, we passed below a corrugated iron sheet, and the walls were dripping wet. This is the only place apart from the entrance where there is an air passage to the outer world, and the corrugated iron has been placed there to protect the visitors from the natural shower-bath which starts up in wet weather. Half way along, another canal goes off to the right, but is partly choked by debris. This is known as the ‘Half Way House’. Behind us, the chain of lighted candles with the rippling reflection in the black water gave us a wonderful sight. Then we became conscious of a hollow, murmuring sound which gradually increased into a roar which became deafening in its intensity. Then we stopped and stepped on to a concrete platform, finding ourselves in a circular cavern.

This is known as the Bottomless Pit. The guide took us to the railings, and with his powerful light shaded behind, shone it down to where a waterfall, coming from directly beneath us, shot down into an abyss. We could dimly see the boiling flood foam on to a shelf of smooth limestone, and then shoot over into blackness. At a depth of 90 feet below us, the water entered a stygian pool, the depth of which has never been ascertained. Colouring was once dropped into the pool, and it emerged 22 hours later at the stream which issues from the ground near Peak Cavern. This points to the existence of a vast subterranean lake. During the aforesaid excavation of the mine, the miners threw some 40,000 tons of rubble into the pool without any apparent diminution of either its extent or depth.

Above us the huge dome towered into eternal darkness. Rockets have been fired to a height of 450 ft, but have not yet reached the roof, neither have skilled climbing members of the Kyndwr Club who have made scientific explorations of these caverns, had any measure of success in that direction, though they have discovered natural galleries high up in the rock. This platform we stood on is 860 ft below the surface of the mountain above. Stakes driven into the rock form rude steps up which the explorers climb to the higher levels. Straight opposite the point where we entered the cavern, another canal runs for 50 yards, and from which is drawn the water for the fall. The miners, during their excavations of the first tunnel suddenly broke through the rock into this mighty cavern, the first time eyes had ever been set on it. They built the arched platform on which we stood, to enable them to cross the black abyss, and continue their work on the other side.

After tunnelling for 50 yards, they came upon a natural waterfall, which flooded the passage, and so took to using boats instead of working in the water. When the level was opened for visitors, it was made higher and broader for convenience. The whole half mile of passage is dead straight, so that from the platform we could see half a mile of glimmering candles. And a fine sight it was, too! An arrangement enabled the guide to shut off the water, so that we could hear him speaking. The infernal roar of the waterfall in this place would, I am sure, drive a man mad in a few hours – the whole thing produced a feeling of awe in us. After a last look at this great hole with its limitless depth, roaring waterfall and great splashes of white and blue fluorspar, we stepped back into the boat, and after what seemed an age, reached the entrance. As we got out of the boat, the guide sat with his cap, and chanted “It is the custom here for the guide to place his cap on his knee”. We saw the hint. Then up the 106 steps to the outer air, which seemed warm after the cold atmosphere below. The air temperature down there averages 52 degrees F all the year round, with little change, and is always pure, for where there is running water there is always fresh air. Although it was dull and raining out here, the light seemed dazzling.

Joe’s cape came in handy once more as we tramped down the road to Castleton, and retrieved our bikes, retracing our steps to the junction with the main road, which we joined, and commenced the big climb up Mam Tor. When we reached the Odin lead mine, we stopped and had a scout round, entering one or two deep, tortuous ravines and scouting for caves, one of which produced abundantly the stickiest, slipperiest clay that it was ever my privilege to sink over the ankles in. Happily, Joe’s shoes were by now in a parlous dirty condition. That’ll larn him! When mooching round the place where the ore was washed, we discovered numerous pieces of fluorspar, many of which we brought home with us. Some of it is like smoked glass with several different tints of blue and green across it. Others are brownish, with beautiful colours like glass in it. More are of a regular parallelogram, in shape, milk-white in colour, and when held up to the reflection of a strong artificial light, I discovered a perfect pattern in green and red and gold. Wonderful stuff, this fluorspar! I think it is a kind of Calcite.

Odin lead mine was worked very successfully by the Saxons, 2,000 years ago, and its stock of ore is still not finished. It also yields about 3 oz of silver to the ton of lead mined, and many beautiful crystallisations are found in it, including blende, barites, fluorspar, sulphate of iron etc. A curious mineral called silkensides, whose properties of explosion when struck by a pickaxe, is well known and feared by miners, is also found here. Another inflammable substance found in this mine is elastic bitumen. It is dark brown in colour, and on being touched by a candle, burns slowly, giving off a disagreeable sulphurous odour. In earlier times North Derbyshire was a penal settlement, and convicts worked in Odin mine. We could have got into the mine proper by ignoring a notice board, but there were too many people about to make it worthwhile (not that we had any qualms!), so we regained our machines and carried on past the huge shaley precipice that gives Mam Tor the appellation of ‘Shivering Mountain’. The mountain is geologically placed just above the limestone, and is composed of shale and micaceous grit in alternate stratifications which speedily decompose by atmospheric agency and fall down the face of the cliff in large quantities. Mam Tor is the old British name signifying ‘Mother Hill’. On a steep pitch on the road we had the pleasure of seeing a motor-cycle ‘conk out’, and for pity’s sake gave him a push up.

At the summit we took the old Sparrowpit road via Perryfoot to Mrs Vernon’s at Sparrowpit for tea, with a grand total of five miles for the afternoon. I was very sorry to learn that the motherly old soul, Mrs Vernon, has ‘passed on’ and the Toll House is now run by her daughters. We started at 5.45pm on free-wheels, swooping down Barmoor Clough to Chapel-en-le-Frith and making great headway past Combs Moss to Whaley Bridge. The earlier rain had damped down the wind, and now the night was one of those still, peaceful autumn evenings. At Whaley Bridge, we decided on a fresh route home, and crossed the Buxton road, climbing uphill for a long time until we stood above a long, narrow reservoir, with the finest view of the Peak I have yet witnessed. The sun was on the great clods of green-brown earth and on the valleys; we could see Hayfield beneath the mountains, Sparrowpit stood out on a ridge at what seemed an incalculable distance away, and all around us were massive steep moors and rounded peaks. A swoop down to Kettleshulme and the Saltersford Valley, another long climb on shanks up the side of the hill into a land-locked valley, while the direction of the road had us guessing. It turned back and formed a huge horseshoe, on which we got many grand views. At the summit we deserted this highway for a bypass that started to ‘fall-off’ the hills down a fine little pass to a wooded glen, then through a brickyard and so into the beautiful little village of Pot Shrigley.

Many winding lanes, all with a downward tendency led us to the main road at Poynton, where we plunged into the lanes again in another (about our fifth attempt) to solve the ‘crossword’ puzzle – a maze of lanes with a way through to Cheadle. We managed it this time, and emerged triumphantly at Belmont just on lighting-up time.

Leaving Tom at Kingsway End, we came back home at a rapid pace by the usual route, arriving home at 9.45pm. Today has been a treat, and we have not by a long way done with the Castleton Caverns. 96 miles