At 8.30 this morning I was spinning along the road again, the Exeter road that took me along the edge of a wooded hill-country and gave me views one side of newly-mown fields and rippling acres of golden wheat, whilst on the other hand many an alluring little lane tempted me to leave my highway. Only once did I yield to the temptation, then I found myself between two blazing walls of roses with the sky above almost hidden by foliage. In twelve miles I reached Cullompton, where I tried to get a 20 tooth freewheel but failed, though I was offered consignments of 18’s. At one village cycle shop I was told that an 18 would do just as well, and when I told the dealer that my gear would jump from 59.8 to 66.4 with a corresponding jump in pushing resistance, he could not understand why, so I took him out and explained, then he fell to examining my mount, confessing that he had not quite “tuk up wi’ them new-fangled thingummis”, and I had to drop my wheels out and in and work my calliper brake for him. Still, it was one of “them there racers an’ don’t like them down handles an’ I think them back forks are too thin an’ I don’t like the looks o’it front un’s either, an’ I’d sooner you ride it till me”. He had the old idea of something massive for a big ride. I got a freewheel of the requisite size in Exeter, knocking a 19 tooth fixed cog off and putting the freewheel in its place. I rode free after that until I reached Corwen on the last lap of my tour.

I paid a visit to Exeter Cathedral; in any part of which one may go without payment, the trustees leaving it to the generosity of the visitor. And a visitor who goes through Exeter cathedral without making a voluntary contribution must be a very mean person indeed. As with Wells, I shall serve no purpose by trying to explain the wonderful works of art that I saw both within and without, so again I will just leave it at that. Exeter was very busy, and is all narrow streets; I was glad when I had squirmed through the traffic and reached the immaculate road on the east bank of the Exe. Topsham was reached, and here I decided to have lunch, a Devon lunch, and just to see how things went I decided to make a light mid-day meal. So I went into a pub and ordered a pint of cider and bread and jam – I am not enamoured of cheese. The bread came in tiny cottage loaves, and was so delicious that I ate six to two pints of cider – bang went my light lunch decision. Topsham is a rather quaint place, more so in the narrow streets leading to the river.

From here my road got hilly, giving me many fine river views, whilst at the foot of each hill was a hamlet that was a brilliant kaleidoscope of flowers. The diet of cider, bread and jam was doing its worst, for the whole road was a drag. Then I dropped into modern suburbia embodied in a seaside resort that resolved itself into Exmouth, and ere long I was on the promenade, glimpsing my first view of the English Channel. Exmouth struck me as being a very usual resort, so without delay I got a boatman to take me across the mouth of the river. It was one shilling to the sandy bar and two and sixpence to the Dawlish road, so I decided to economise and had a bobsworth. But had I known ! Came nearly an hour of collar work over soft dry sand until I was reduced to the consistency of butter, for it was a hot, dull day. Thus I reached Dawlish, which carries the usual brand of the resort, but is bounded by magnificent cliffs and jutting teeth of rock, a glorious first glimpse of the South Devon coast.

The road was all uphill and down dale; from the summit of each hill were wonderful sea and coast views. My ideas for a thrust into Cornwall that day went by the board, for it goes against the grain to rush things amid this kind of scenery, even if the road allows it. ‘Billy J’ was right when he said that 70 miles is a good average for a hard-rider in Devon. In two miles I walked up three long hills, then unclimbed them all in one headlong descent into Teignmouth, another ordinary resort with an extraordinary coast. Out again after crossing the river by a long wooden bridge for which I paid one penny and up again until I looked down on the river mouth in which were the low grey hulks of three warships, the golden bay and guardian cliffs and islands of weather and tide worn rocks of fantastic shape, with behind it all the rolling waters of the channel dotted here and there with ships. So, with sea or land views I swept inland to Newton Abbot and Torquay.

I am correct when I say ‘inland to Torquay’ for I had not the slightest desire to go scouting around the promenade which is like the ‘prom’ of every fashionable resort only more so, and in my hatred of dresses, ‘prom’ adornments and piers with their quaint amusements, I was willing to sacrifice whatever scenic attraction there might be, to get away. That is why I crept un-ostensibly round the back of Torquay, and came to rest at a CTC place on the outskirts. The people came from Lancashire and were delighted to see me. We fell to talking about ‘up north’ and about cycling matters, for they were old cyclists, retired and keeping a beautiful boarding house, which, to keep memories green, they have called ‘Dentdale’. I had a right royal tea, a real Devonshire tea with extras, and yarned about things until the time got late, and I reluctantly tore myself away.

A few minutes later I descended to Cockington. Situated in a narrow valley, it is everything that guide books and picture-postcards depict it to be – and more. The old forge, charmingly set in a narrow lane hedged by equally ancient thatched cottages, whose stone walls were brown and moss grown, whilst over the garden walls hung roses and intertwining creepers, the tiny, musical stream and the overarching trees made up the sweetest rural picture I had seen for many a day. The hamlet was quiet and unsullied by its proximity to a popular resort. I crept down the valley, by the musical stream, along a lane whose leafy walls and roof shut out the light and threw the road in semi-darkness. A Devonshire lane ! Is there anything in the world so beautiful ! Is there anything that can show such treasures of nature as the hedgerows of wild flowers and such scents as a Devonshire lane !

My lane took me to the tramlines and promenade of Paignton. Only one thing did I see at Paignton that stamped it as different from the ‘rest of em’, and that was the tropical plants that grew in the gardens. I might have been suddenly transported to some Indian or Hawaiian garden city, so different everything appeared. Beyond here, I was pondering on a moorland-like heath, at the Brixham-Dartmouth fork roads, on which way to go, when a farmer came up and I got into conversation with him. He was a right old West Country chap, swarthy and stolid, and speaking in the drawling tone typical of this county. When he had ventilated his views of every topic under the sun, I asked him about the best way, and if Brixham was worth seeing. He told me that there was nothing at Brixham and advised me to carry on to Dartmouth, which I did, though I later learned that I had missed a glorious bit of South Devon. A long, long climb took me to a viewpoint from where the beautiful river Dart lay below me with its convoy of craft – including two ugly, grey torpedo boats. On the long easy descent to the river, magnificent moving pictures rolled before my eyes.

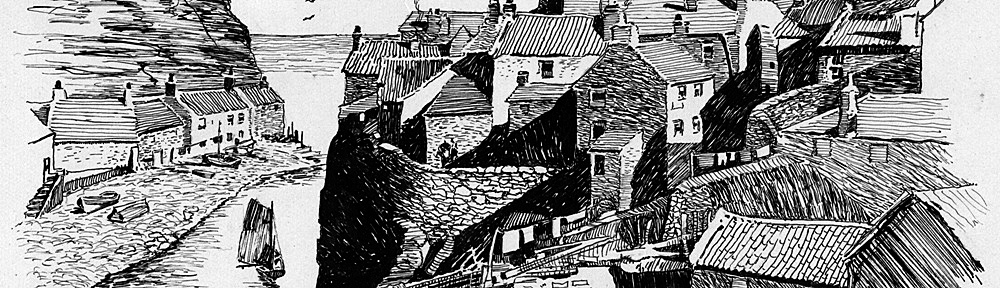

They have a ‘floating bridge’ across the river, propelled to and fro by a steam engine, which, if noise is a virtue, must be positively bristling with good points. Anyway, it rolled me and couple of motorcars across and charged me fourpence. Dartmouth is a breath from the past, recalling vividly the days of those bold thieves, Drake, Raleigh, Blake and other ‘British Mariners’, but recalling them in a romantic, history book way. Ancient cobbled alleys with the houses quaintly built, seeming, in some instances, ready to topple onto each other, a sleepy, old-fashioned little quay, and a castle and church combined, so to speak, a place where, (including the coast) one would like to potter about for days.

But my path, though flowery, and strewn with roses, had a few thorns in it. I was already looking like a Red Indian with the heat of the two days before, and I found washing a painful, delicate operation, whilst my arms and knees were peeling and I dared hardly touch them. Then each day was as much as anything one long search for water, for I had acquired a thirst that knew no limits. Also, two days and a half of hard-riding on ‘fixed’ had somehow made me saddle-sore, and I knew that another day or two would be required to alleviate it. Still, when one is amidst such scenery as I was, these ‘thorns’ are nothing against the pleasures one finds.

As ever, the road was hilly from Dartmouth, and this hill was an extra special one, the narrowness and depth of the lane making it like an oven. On the top lay the little village of Stoke Fleming, where the walls were covered with roses and the gardens a blaze of glory, The church, like several others I had seen had a half-round tower, castellated and no spire, similar to the narrower of the round towers of Norman fortresses. So far as I can make it out it is a style peculiar to the West, for I don’t recall seeing one north of Somerset. The scenery became more enchanting; now I looked down on a glorious little cove of brown tinted cliffs, either rising sheer from the water, or weathered into fantastic shapes, pinnacles and arches in islets of brown rock from a green, clear sea. A sudden breathless descent took me to the cove, where was the tiniest of sandy beaches, and a tiny hamlet deep in a glen that owned a thousand summer shades of leaf and flower, and through which ran a crystal-clear stream. And its name was….Blackpool ! I could not imagine a greater contrast than this infinitely beautiful, unspoiled cove beside the big, dismal, unattractive Lancashire seaside namesake, and I fancy should not hesitate if it came to a choice.

Another precipitous climb through hot woods put me once more on top of the cliffs, and with a view westwards of a stretch of golden sands behind which was a marsh where the road ran across, and eastward of magnificent cliffs, I tumbled down again, round many a hairpin bend, to sea level – on the first rough road of the tour. A dead level two miles took me across Slapton sands to Torcross, where I turned inland for Stokenham. Then, in rapidly gathering dusk I had six lumpy miles, through many an attractive village until I came to a town built on a very muddy river, with a quay on which all the beauty – and otherwise – of the town walked about – Kingsbridge. As I was not attracted with it, I stopped to weigh up the chances of making a seven mile blind to Modbury (it was now 9.45). Just as I was about to make a start and risk it, up came a cyclist, who, divining that I was in search of a place, suggested that we both ‘pig in’ where he was staying. So I gave up my thoughts of Modbury, and away we went and were soon fixed up. He is a Manchester chap on a fortnight’s pottering tour to Land’s End.