OVER MOEL SYCH

September, 1932, like ‘the Lady April’ had her full share of moods. One associates this lovely month with bountiful harvest, with sunshine and blue skies, a period of settled weather through which creeps approaching autumn. But this month was tearful, sunny, shaken by gales, frost and calm and hot, mixing all the varieties of our English climate into an April pot-pourri.

September, 1932, like ‘the Lady April’ had her full share of moods. One associates this lovely month with bountiful harvest, with sunshine and blue skies, a period of settled weather through which creeps approaching autumn. But this month was tearful, sunny, shaken by gales, frost and calm and hot, mixing all the varieties of our English climate into an April pot-pourri.

On the third Saturday afternoon I crossed Chat Moss under the bluest of skies. Little puffs of white cloud floated slowly along, and the sun was hot, like full summer. I moved quickly, as one who has many miles to cover in few hours, for Jo and Fred would be awaiting me ninety miles away, and they had promised to have a grand supper awaiting my arrival. Although adding a few miles I took the Tarporley road in preference to the main road by Chester and Chirk. I was on roads that make hurry possible. The little hills and long levels of this familiar highway, with a light breeze behind, kept my feet circling quickly; unconsciously, as my mind travelled with my eyes along the hedges and into cottage gardens. Twelve years before I had first timidly crept along here in a mood of discovery, my wondering senses in a growing delight of new sights and scenes, and now I appreciated it just as much, looking forward to the next bend just as keenly, though I had turned that bend a hundred times. There is something great about the way one can travel the same old roads so many times in the same spirit of enthusiasm. It would break one’s heart to know that never again could one’s face be set towards them. Death were better!

I appreciate suitable company, but when an alien voice breaks upon a mental ecstasy, I curse silently, and answer with an eloquent semi-silence. This voice announced a desire to be listened to for the next ten miles to Bunbury – ten of the loveliest, most expectant, miles. At least he had a turn of speed, so we whipped along until the lane which led him to his lady-love appeared, and I found myself alone again. Eleven miles to Whitchurch, easy, glorious miles, with the red hills of Peckforton to the west, a roaming place on many a Sunday with Tom in the past nine years.

[Now alas with his real buddy, Tom Idle no longer. One year earlier, Tom Idle had stepped up to the altar and married a Welsh girl and presumably settled down in North Wales, for we hear no more about him, and my computer searches have thrown up nothing. Charlie must have been gutted for in his record of cycle runs kept for 25 years, just two words against the entry for 28 September 1931, “Tom’s Wedding”].

Two miles from Whitchurch, on the Shropshire border a tandem pair caught up to me, and boasted how they had come all the way from Burtonwood by St Helens. I agreed they had done a good ride (almost as far as I had) but when they complained of the hard road I laughed. “You’ll have harder yet!” I forecasted, as, entering Whitchurch, I sent them on to the Wellington road, myself turning westward in an oblique slant towards the Welsh border.

A few miles along the Ellesmere road I stopped for tea at a cottage all but hidden in a long riot of a garden. Fifty six miles were good enough for an afternoon ride. Now the level waters of the Mere, the narrow streets of Ellesmere, the crossing of the Holyhead road at Whittington, where the great towers and moat of a feudal castle add romance to the place. I have heard it said that here was born the poor boy who dreamed of London streets paved with gold, and who became the Capital’s greatest Lord Mayor three times. Behind the fairy story of Dick Whittington is the germ of truth. Saturday night in Oswestry, narrow streets, great crowds, dusk – and the road again, beating south again as the moon came up.

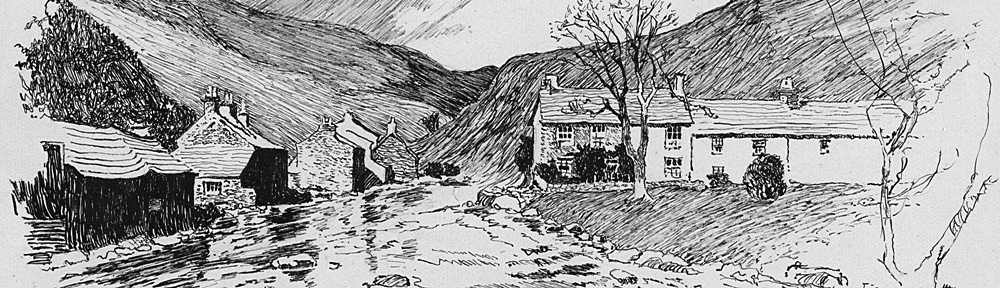

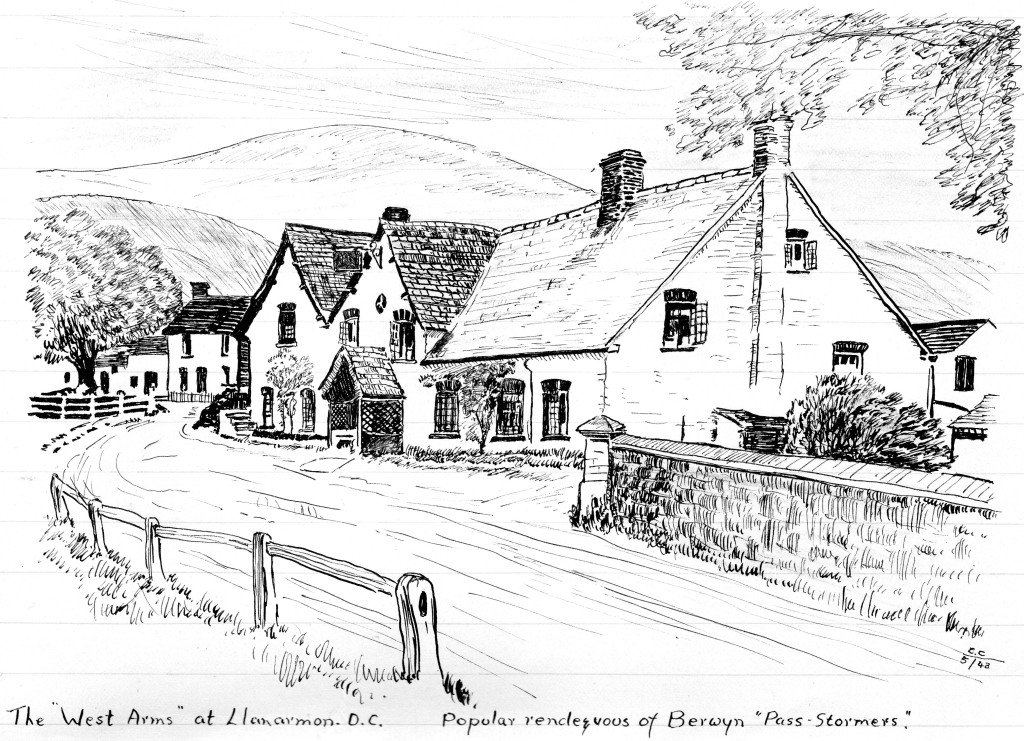

There is a cross roads at Llynclys, and there I turned westwards, between low hills, growing higher, with a river growing swifter, clearer, the Tanat river. Lamplit, in moonlight, a road almost level, are ideal conditions of travel, and my wheels sped for many miles, veered at last from the main valley, and came to Llanrhaeadr-ym-Mochnant, the deep village under the shadow of Berwyn. The last four miles above the Rhaeadr stream would shatter any dream of speed, the ninety miles in my legs began to tell their tale, and my mind was occupied with the promised supper, now so near. I had earned it, I felt. After an array of good things there was to be plum pudding overspread with custard. Two helpings. Then I would lie back in supreme comfort when it was over, and smoke a reminiscent cigarette.

There was Pistyll Rhaeadr ahead, a tall black cliff shutting up the valley, with the white streak of water upon it, a farm, even a group of great fir trees dwarfed by this, the highest waterfall in Wales. On the last hill above the farm I turned aside through a gate, along a good green track, and at the first bend I saw our two tents romantically placed across the track – the only level spot in that region. The tents were unlit and deserted; inside I saw the rest of the kit hurriedly thrown down. Leaned against the steep moor were the two bicycles. Then I saw the table. This was a huge, flat-topped rock about two feet high. For lack of other space Fred had encircled it within the tent, one large section protruding from the doorway. And even the table was bare!

My light had evidently been seen, for there were voices calling me from somewhere far below in the bottom of the valley. Some time later two overheated cyclists burst through the bracken below the path, carrying a milk can and canvas bucket. They had foraged the farm without luck, and taking a short cut along this branch valley had become tangled up in fences, heather, and bog.

Long afterwards the pudding appeared, if not hot and steaming, at least warm on the outside. Of custard there was none, but we sat round our rocky table in the bright moonlight and ate, and drank coffee ad lib, and yarned. The ‘table’ effectively stopped us from closing up the tent, so Fred and I slept curled round it.

Cool and sulky morning. How often has serene eventide lulled our last thoughts into a golden morrow, to find, on awakening, a transformation, a promise falsified? The rain barely held off while we packed our kit away, and as we moved on in single file along the narrowing path the rain came, “gentle as the dew from heaven” at first, then steadily settling in, in true Berwyn fashion. At a stream the track ended, the trouble began, the usual becaped struggle over tufty grass, tangly heather, into the wild amphitheatre in which lie reed edged, gloomy Llyn Lluncaws, under the frowning brow of Moel Sych. As this was our third crossing we feared no false moves, and skirted the lake, striking by the easiest route, towards a rugged summit ridge directly north.

There is no easy way, with heavily laden bicycles that first summit was reached by sheer hard graft. The cumbrous capes, the slipping grass, brought us down in turns, and we fell heavily. The heather tugged at us. This ridge gave a view into the deep jaws of Maen Gwynedd valley, across which the rain slanted. Now the climb was toward Moel Sych itself, aslant the main spur, again a devilish struggle, this time with loose scree to cross, over which one looked down hundreds of feet of rock to Llyn Lluncaws. I was well ahead when I saw Jo suddenly slip and come down, bicycle and all on the very edge of the cliff. Fred dropped his bike and made a grab, hauling her clear, with not a foot of space nor a moment of time to spare. Dangerous moments! No injuries, just a word of thanks, and once more the slow, wary plod with shouldered bikes. These things are not remarkable, just the rough chances of the hills which the three of us are willing to take.

The summit cairn of Moel Sych, yours truly aged 15 in shorts, Fred Dunster left of picture and H H Willis seated and standing behind another RSF member known only as ‘Bart’. This picture and story incidentally, complement the release on this website of the story ‘Behind the Ranges’, released on 21st of January this year. This ‘summit’ took place at Easter 1956, on the occasion of the very first RSF Easter Meet. Below you will see a picture – an old one – of Charlie in a tartan shirt taking tea with our RSF President Sir Hugh and Lady Rankin at the same Easter Meet.

The summit cairn of Moel Sych, yours truly aged 15 in shorts, Fred Dunster left of picture and H H Willis seated and standing behind another RSF member known only as ‘Bart’. This picture and story incidentally, complement the release on this website of the story ‘Behind the Ranges’, released on 21st of January this year. This ‘summit’ took place at Easter 1956, on the occasion of the very first RSF Easter Meet. Below you will see a picture – an old one – of Charlie in a tartan shirt taking tea with our RSF President Sir Hugh and Lady Rankin at the same Easter Meet.

A tiny ‘gateway’ of a gap in the rock heralded the summit, and hot and winded we threw ourselves down. Our altitude was 2,715 ft; the great backbone of Berwyn heaved away with its many ribs eastward. Llyn Lluncaws lay a thousand feet below in dark reflection, a pear shaped mirror. On the northern side, miles of bog-ridden moorland slopes wasting away into the rain. Nothing more, except the sense of vastness and a great solitude.

Now the long descent, three miles and more of wary treading. Again we were fortified by past experience. The exultation of winning to a difficult summit is apt to vanish when the subsequent descent becomes so involved that one wearies of even hoping to get down to sane, hard roads again, and we shall never forget such an experience in rain and bog when every step had become a labour, every movement an effort, every vista a morale-shattering vista of endless acres of shaggy tussocks emphasised by boggy runnels that were more to be feared than the bitter tops. That is when one begins to long for the easy pleasure of just lying down and perhaps sleeping, sleeping on and on… for ever. We had learned the way, striking down the slope of Nant Esgeiriau, remaining sufficiently above the watercourses to avoid shouldering the heavy bikes again. The rain ceased – perhaps we got below the clouds – and at a farmhouse called Rhuol we reached the old road which runs up Cwm Pennant to join the Milltir Cerig. There we tried to make ourselves look less disreputable, changed into dry stockings (but kept on soaked shoes), started the primus stoves, and did ourselves well on the rest of our food.

Jo was the lucky one for once; she had a day or two to spare, and gathering together our kit, bade us au revoir, to penetrate deeper into Merioneth. Fred and I, with over eighty miles yet to cover, turned our wheels eastward from Llandrillo, through the vale of Edeyrnion to Corwen, laboured over the Llandegla Moors to a belated tea at Chester.

In the quiet glow of evening, with September once again in her golden mood, we planned our next hill-crossing, little dismayed by the hostile reception Moel Sych seems to hold against our persistent wooing.

By the way, Moel Sych means ‘Dry Hill’.