Scottish Highlands Part 4

We awoke to twilight fog, though my watch betrayed morning well advanced. Geldie Burn chattered past; the northerly wind brought the endless drizzle, and only bog and spears of coarse moorland grass lay to the near limit of our vision. Over a humble breakfast of stewed raspberries and custard we studied our Ordnance Survey and found we had over-run the path we wanted. Ahead lay Geldie Lodge; a short walk over the footbridge revealed it dimly snuggled in a fold of the hills, deserted. A little cairn of stones some yards back gave us the clue, and after that the path barely existed; tiny cairns were spaced, each within sight of the next, and between them reeking stretches of bog. We thought ourselves the only beings there till a herd of deer suddenly came out of the mist not twenty yards away.

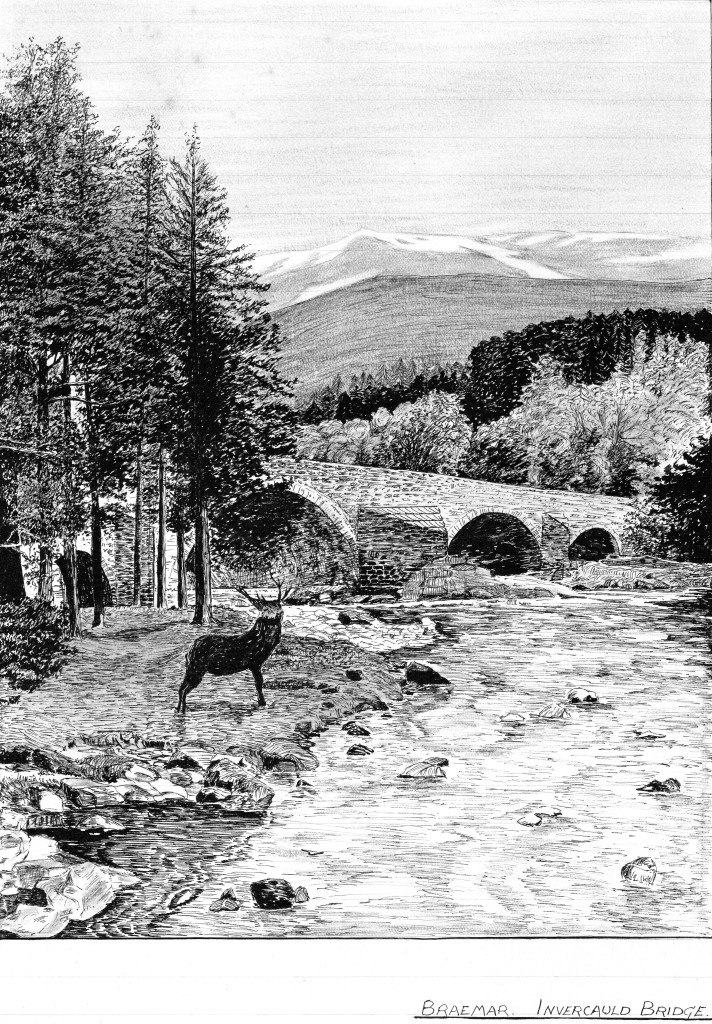

Their leader, with a quick toss of antlers, roared a warning, and in a flash we were alone again. We missed the cairns, groped about bewildered over crumpled hillocks intersected by innumerable streamlets, finally picking up our route again by the River Feshie flowing in our direction. The impetuous torrent of the swollen Eldart barred our path, thigh deep, and desperately difficult to ford with the laden bicycles.

From that point the scenery took on a new aspect. The valley deepened, narrowed, the river turbulently entered a gorge, and rowan trees clung to crannies in the rock. We came to the brackish foot of a fine waterfall, though the stream provided another tardy crossing. Indeed, the noise of water came from every side; cataracts flinging themselves out of the mist, the Feshie water plunging along the bed of the ravine, and every streamlet brawling along impulsively. A slanting curtain of heavy rain sweeping up the glen was the last; behind it sunlight filtered through the vapours, and the mist rose to higher places, to wreathe bulging crags, to hang like steam in the rock-choked corries. Beauty and grandeur crowded together. Beneath scarred cliffs tall red spruce trees were dwarfed, and the green carpet of turf sprang easily underfoot. An added touch of the wild came to us as a great big bird with hooked bill and massive beat of huge wings rose suddenly and sped into the wastes above. We are sure it was a golden eagle; we like to think it was. Sometimes where long-forgotten storms had wrought havoc amid the trees, the path was hard to traverse. In one place a hundred yards of rock had collapsed across the path, and we had a rough time getting across. In Glenfeshie forest we saw men with guns, and we knew then the reason for the hasty departure of the herd of deer on Cnapan Beag.

Loch Tulla

Amongst the pines near Feshie Lodge we explored a derelict chapel, an unpretentious place, but on the crumbled plaster above the fireplace was the figure of a deer, the remnant of a painting by Landseer. Glenfeshie forest, a shaded parkland of fir and spruce, with wonderful turf, was a pleasant place for lingering. A footbridge close by the large garden-embowered Feshie Lodge, saved a contemplated struggle through the swollen river, and a firm, real, road was reached close by the Lodge gates. There was a fork-road towards Kingussie – ‘the mountain road to Ruthven’, with a couple of deep fords which no longer troubled us, and a backward view which must inspire in clearer weather. We saw the mists once more creeping down from the Cairngorm heights to fasten Glen Feshie and the grim bogs of Geldie in premature twilight. Ahead the richly wooded Spey valley curved towards the brown Monadhliath barrier.

We tumbled down past the old barracks of Ruthven, relics of General Wade’s day, and on a good road came to Kingussie.

Our stores were quite depleted, and two shillings are little enough to build up further supplies. Luxuries had to be ruthlessly cut……… I went smokeless. Jo haggled over the price of plums – we still had custard powders, and with bread and milk, and paraffin for the stove, were assured of one good meal. That was as far as we worried. With one penny left we swaggered out of Kingussie, after a talk with a Wigan clubmate en-route for Perth and home.

From the next village of Newtonmore, still beside the Spey, we had a lovely run past the old battlefield of Invernahavan, past deep woods and winding about high rocks to Laggan Bridge, where branches the old Wade road, tracing the higher reaches of Spey on its ruined way over Corrieyairack Pass. One day we mean to cross the wild, bulky hills of Monadhliath. Into Strathmashie our road led us as evening came, and we found a perfect camping place at a waterfall where the Mashie water crosses the road. There we dined well on our simple fare, and spent the idyllic hour of dusk at the edge of the fall, careless of the whole world.

The next morning we were up early and soon awheel again, as, to put it mildly, our breakfast was not sufficiently complicated to dally over the cooking or linger at the eating. We soon reached Loch Laggan – and the first of the road gangs. The men worked with muslin over their heads to keep at bay the attacks of McMidge, which came in clouds to pester the life of, and put to flight anyone who dared to stop for a moment. The state of the road was shocking; in the process of neglect prior to being reconstructed, which work was in progress in places, but nowhere far enough advanced to make travel easier. So we crawled along the great length of Glen Spean, eyes glued to the awful surface, blinded and choked by dust from passing vehicles, with ever and anon the noise of road gangs in our ears. At Spean Bridge Jo urged me to go on ahead, for the possibility of early closing day (Wednesday) at Fort William had dawned on us, and the idea of waiting penniless on the doorstep of a locked post office until the morning did not appeal. She would follow, she said, and practice en-route the subtler and more appealing notes of the songs we were to sing, should the remittance not materialise. On the earlier part of the morning’s ride we had achieved some measure of harmony, which might – or might not – induce the wily Scot to part with a copper or two, if only to see the last of us. The extra bits – the ‘down and out’ appearance, the shuffle along the gutter, would come with experience no doubt!

In a race against time I crashed over the remaining few miles into the town of our hopes, entered the Post Office with bated breath on the stroke of twelve, tore open feverishly the waiting letter, from which tumbled twenty-five shillings. We were saved again! The business of the Employment Exchange was concluded, and when Jo came down the street the sight of me with a cigarette at once assured her. There and then we bought a great supply of food, with a few delicacies to celebrate, went beside the sparkling waters of Loch Linnhe, and had such an orgy that it dissipated our new stocks.

The level road alongside Loch Linnhe had the gloss of new surfacing, heavenly to ride after Glen Spean, while across the water the many headed hills of Ardgour and Sunart were superb in the clear air. Our troubles however, were not over. My front tyre, badly weathered in a summer of wandering, swelled enormously, until at Onich, just beyond Corran Ferry, I could go no further. A garage man gave me a large piece of old tyre which I stuffed inside, and thereafter rode with a constant bump at every circuit of the wheel. We crossed the Ballachulish Ferry, a wonderful spot near the foot of Loch Leven, with the salt tang of the sea in our nostrils, and in our eyes the panorama of the Lochaber giants heading the loch, the wild Glencoe peaks ahead of us, and the sunlit hills of Ardgour across the water.

Glencoe, too, was in the throes of reconstruction, again nowhere advanced to give us much comfort. There would be a short bit of broad, finished asphalt, then a plunge back to the steep old road, now a hundred times worse from the heavy traffic engaged on the building of the new road. We realised, too, that again we were foodless, and many rough miles from the next village, but down came a van which we stopped and obtained ample supplies. Eggs were obtained from the wife of a road worker, and she refused to take the pay. As we mounted higher, great clouds sailed above the precipitous flanks of the pass, and the sun, shining at intervals, played search-light fingers into the hollow. A wild, desolate place, Glencoe!

At dusk we reached the summit of the pass and sought thereabouts for a camping place, but not a green, firm patch could be found in all that waste of rock and bog; even the wild head of Glen Etive, which we traversed for some distance, had nothing to show. Casting about, we eventually found an exposed patch on the Loch Rannoch trackway quite close to Kingshouse Inn.

The magnificence of our site was more apparent the next morning when the rising sun reddened the bulging cliffs of Buchaille Etive Mor, and before the heaving Moor of Rannoch around us was properly clear of the dawn, all the craggy peaks were bathed in brilliant warm light.

The new road-to-be across Rannoch Moor had not yet been commenced, and the old road, gone all to pieces under the burden of traffic far beyond its capacity, was a hopeless rut or a mass of stones over which we jolted the whole day, over Black Mount and Ba’ Bridge to Loch Tulla, the few trees about the Loch intensifying the wastes of Rannoch which rolled east in bog and water as far as our horizon. There were five peaks across the Loch as high as Snowdon; behind us, west of Black Mount the group dominated by Stob Ghabhar and Clach Leathad rose higher still in the blue sky, dividing our attention between fore and aft and the rutty road. At Bridge of Orchy the civilising influence of a railway line sobered the road a little, which took us into sedate Strath Fillan, by Tyndrum to Crianlarich. Hitherto the places had been hardly more than names on the map, but Crianlarich had a hotel, a church, houses, a railway station, and more than these things to us, a good road down green Glen Falloch back to Loch Lomondside. We were weary of the perpetual gyrations and skids of the old tracks, a little anxious for our tyres, particularly my front one, which was bulging again in an alarming manner. In the afternoon we fared better – slightly – on Loch Lomondside, the entrancing, unspoiled beauty of the upper parts, a fine farewell to the Highlands.

Just below the foot of the loch, at the beginning of Clydeside’s environs is a place called Alexandria, where my tyre finally gave up the ghost, and a convenient cycle shop fitted me up with a Dunlop ‘Champion’ for three shillings and sixpence. Our exchequer was again beginning to rest lightly in my pocket.

For the third time in a little over two weeks I was at Erskine Ferry again, and once again I tried to find the ‘recommended’ route to Carlisle (avoiding Glasgow), this time with more success, and dusk found us near Strathavon, at a farm where we were readily given a pitch for our tents.

The southerly wind, which had given us such a doughty tussle on our way out veered north during the night, and we had the dubious pleasure of facing it once more across the rumpled central plain, by Lesmahagow, to the pleasanter Clyde country, and the original road to Crawford and over Beattock, sometimes in a wild flurry of rain. At our first campsite together at Ecclefechan we had left one or two superfluous articles, and we called to recover them. The woman of the house was very pleasant. Would we like a drink of tea? We agreed but did not expect the relatively sumptuous feast which was brought to us. With our feet under a table for the first time for a week, we decided that the good lady deserved a fair return for her efforts, and I went to foot the bill a little anxiously. The three shillings she charged was very reasonable……… but how slender was the remaining burthen!

That Saturday evening we prowled round Carlisle market, seeking out the lowest possible prices for our supplies, and as we slowly left the City behind, boring into a golden, windy sunset, the bulk of our food-bag was bread, and a little oatmeal. There was a pound of plums for stewing too. Plums were remarkably cheap that season. The usual, inevitable custard we would have to forego. Aslant of one of the interminable hills towards Penrith lies the village of High Hesket, where we obtained a camping site, and where, from sheer lack of money, we had to thank the farmer profusely next morning, and beat a hasty retreat before any thought of payment entered his mind. In fact, High Hesket hill was topped in grand style, almost before our last word had reached him!

This last day was boisterous, with sharp storms, and, it seemed, ever so slowly, we lifted ourselves over the altitudes of Shap Fell into our home pastures. For the final meal near Lancaster we enjoyed bread and jam without even butter, and our journey was completed with the same two half-pennies as on that rough ride between Kingussie and Fort William.

At the height of a great industrial depression I had completed a round trip of about 1150 miles, half of them with Jo. Between us, our total funds had not been more than three pounds ten shillings, yet the ubiquitous bicycle had taken us through the heart of the Scottish Highlands, into a wilderness where yet the snow lingered on the mountain tops, a country far removed from the stagnant, crowded life of the great industrial regions of Britain.

We had for the first time in my life, been introduced to that land of Bens and Glens which in the future was to give us to give us our happiest days together. In those years then unborn we were to look back to that week when the borderline of complete penury never marred our complete happiness, where our unity and freedom were treasures of which we had ample store.

[ Footnote] As the reader will appreciate, the last paragraph was added years after this tour. Charlie and Jo spent many holidays in Scotland, and, with the colour transparencies which he was one of the first to start taking immediately after the war, sustained his magic lantern shows through many a winter clubroom night. To this day they rest in my house loft, unseen for thirty years, thousands of them. Scotland’s magic, in the high and lonely places, never faded for Charlie and his wife, and we must be grateful to him that he was minded to set it all down for posterity. Charlie died in 1968, Jo some seven or eight years later.