Upper Ribblesdale was in angry mood. The mountains were cleaved into ridges by grey mist-banks, borne on the cold easterly winds; the trees, deprived long since of their clothing of leaves stood alone or in open groups, naked and miserable; the brown moors even seemed to sulk at the day, and here and there terraced limestone, dirty grey, ran with water. There were hamlets that huddled as if sheltering each other, but with scant success, and isolated farms that pressed their stone sides against the wind and the rain. The road was hard; interminable little hills ascended to points where the free wind swept across unhampered, and where the rain it bore along in a horizontal track stung like a whip.

Upper Ribblesdale was in angry mood. The mountains were cleaved into ridges by grey mist-banks, borne on the cold easterly winds; the trees, deprived long since of their clothing of leaves stood alone or in open groups, naked and miserable; the brown moors even seemed to sulk at the day, and here and there terraced limestone, dirty grey, ran with water. There were hamlets that huddled as if sheltering each other, but with scant success, and isolated farms that pressed their stone sides against the wind and the rain. The road was hard; interminable little hills ascended to points where the free wind swept across unhampered, and where the rain it bore along in a horizontal track stung like a whip.

I have seen Ribblesdale like a gem in summer, all gleaming under warm skies and kindly sunshine. The moorlands, brown as they always are, have been alive with living beings like the virtuous curlew and the hoarse grouse; lambs have skipped and dozed and bleated with thin throats, and their black-faced parents have foraged the coarse, spare grass with undisturbed tranquillity. In summer time the riverside fields have yielded their lot – hay and wheat, and where triumph from the encroaching moorland has been greater, other crops have flourished. The trees too, even those isolated survivors in windy spaces, have held leaves to show the world they live, and round about the farms men and women, with noise and bustle and many a shout have plied their endless fight against nature. Little winds from west and south have helped us up the dale, and we have greeted the country folks with a smile or a ‘good day’.

This day on the threshold of February made us wonder if summer could ever come here again. Perhaps it was that human folk had given up their losing fight and gone away to the warmer plains for ever. We had no place there, the wind seemed to cry, but we continued just the same, for man can defy the elements and push himself against their will. He loved to do it sometimes; in the creeping, tortured road beneath us he had set a permanent seal to his defiance; down below, in the dale, his road was strips of metal on which his vehicles ran with speed that defied the very easterly gales. We met a burly farmer down the road, and knew then that Man only rested behind stone walls. Spring and the bleating, frolic-some lambkin would come again; the sparse fields would nourish growing things that spelt life to man and beast, and the bustling and day-long toil would come with the sun.

This day on the threshold of February made us wonder if summer could ever come here again. Perhaps it was that human folk had given up their losing fight and gone away to the warmer plains for ever. We had no place there, the wind seemed to cry, but we continued just the same, for man can defy the elements and push himself against their will. He loved to do it sometimes; in the creeping, tortured road beneath us he had set a permanent seal to his defiance; down below, in the dale, his road was strips of metal on which his vehicles ran with speed that defied the very easterly gales. We met a burly farmer down the road, and knew then that Man only rested behind stone walls. Spring and the bleating, frolic-some lambkin would come again; the sparse fields would nourish growing things that spelt life to man and beast, and the bustling and day-long toil would come with the sun.

There were places in these hills that never heard the wind, that knew no light but the occasional candle of the timid humans who knew their sufferance was only in hours what ages had built and ages did not destroy. Now, when Winter ruled above, there was no place for man; only swirling water that did not stay, and darkness that never moved. There were vast places where light or man would never go, and in them beauty grew unknown…….fated never to be seen.

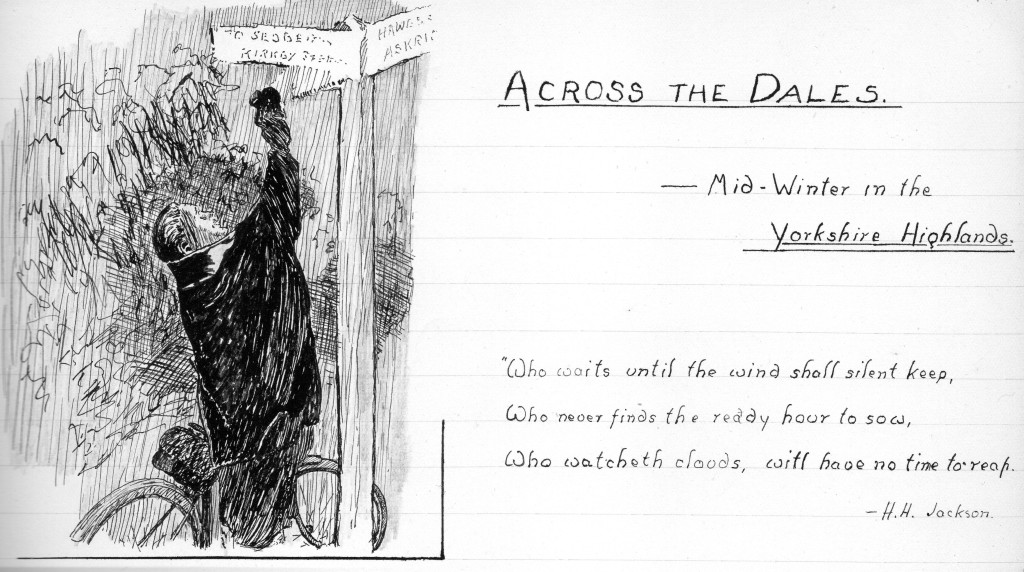

Can it be wondered then, that as we slowly pressed our way to Ribble Head, the elements and these thoughts occupied our minds. We had been out at morning, and had faced those elements all the day except for a rest at Worston near Clitheroe. Dusk overtook us at Ribble Head, where we turned for Hawes, along a metalled road that was abandoned to the night. A good, metalled road, yet deserted as the windy fell tops themselves. Man had graded it carefully, lest his road across those hills should not bear its worth, but his winding tilts were devilish hard that day, and we were glad to walk long stretches of it. There was snow near the summit and the cold rain held sleet. We passed the fork-road where through the mist a single finger-post pointed ‘Dent’ towards the northward wastes, then in a little while a window gleamed its light and we sought shelter and tea there, at the ‘Inn’ on Newby Head.

A hundred years had brought two changes there. We had tea at an old, misused sideboard in a large room. In the open hearth a peat fire burned but did not spread its warmth to us; the floor was flagged and sand-sprinkled; the roof (or ceiling rather), was supported by massive beams of oak; food lay on the bare table – the remains of a meal; and three young children crawled on the dilapidated rug that constituted the only floor covering or ran up and down the sanded floor with iron-shod clogs. The two men-folks were busy giving each other haircuts all the hour we were there, while the woman; middle aged wife of one, sat sewing clothing that would long have passed out of ken in town. The two changes – a Ribble bus company timetable, and a fine wireless set that gleamed new in such a careless, ancient room. There, at 1,400ft, miles from the nearest village and isolated by gale-swept moorlands, we heard the sports results from throughout Britain, the weather report from Manchester, and the news bulletin relayed from London.

We went out from that big room cold, but the outer void was colder. It was black, welded into a frozen whole, in which the Nor’easter played unhampered. For a space we could not pierce the black because our acetylene lamps had frozen; the first blue flame announced our success at last, but we had only shifted the zone of activity – we almost cried with frost-bitten fingers. Our haste to get down to the sheltered valley, five miles down the night received a jolt when brakes too easily jammed the wheels, which slid quickly off the perpendicular. The road had become a sheet of black ice. Two miles below the wind growled to a silence and the road was again wet. Rain began. The steep end of Hawes with windows pale through curtained light assured us we had come to rock bottom at the head of Wensleydale. We only required that assurance of Hawes, and we left the bulk of its one main street behind with less than a glance. We crossed the dale to Hardraw. The Buttertubs Pass begins its ascent at Hardraw (you can hear the roar of the Force from the buttressed road); I had crossed the pass once, on a broiling Bank Holiday weekend, when crawling cars crossed too and people covered the moors almost like maggots on choice Limburger after long isolation, but not so admirably camouflaged as the insects are. We expected nothing moving on the pass, except the northeaster, and its sleet, and we were right. The gradient is easiest from Hardraw, but at a thousand feet we reached snow. A sludge at first till the Pass proper, then the snow deepened, hung on our feet, jammed our wheels. The going got hard at 1,500ft, for the Nor’easter was gusty with frozen sleet slashing at us, and the deepening drifts under-wheel. A mist came down or else we climbed up to it, and our lights came back at us. The road then was buried with nothing to tell its boundary from the moorland bog, but the faint track of a cart that had crossed hours before. We were lucky, for that was our only guide to the summit. Our slow plod was rewarded with a final drift three or four feet deep through which we almost swam to the cart track, faint but still faithfully present on the other side. That was the summit at 1,726ft.

The descent began, hardly easier, but for a time sheltered. I could smoke a cigarette at last! The snow underfoot got us in the legs which became heavy, wearied. On the right a grey gaping Nothing kept us to our solitary cart tracks; on the left the tousled white of the bank must be eyed with suspicion. Once, in a flash of memory I recognised a landmark that had seated a motoring party at tea one August afternoon, and to test my memory I found a loose piece of independent rock and threw it into a snow cornice. It sped through, awakening a hollow cataclysm of noise in the depths of the hill. “One of the Buttertubs”, I said to Fred, who grimaced and suggested a closer attention to the friendly cart tracks. The cart tracks certainly saved us from complications. Half a mile further down the road shook itself clear of snow and slid down like a precipice to the Swaledale road at Thwaite, just above Muker. Four miles, four hours!

The next three miles climbing round Kisdon Fell put the finishing touch to us. We admit quite frankly that we were ‘knocked’. Cathole Inn at Keld was hailed with relief. It was built with the one purpose to receive us on that Saturday night. The dales-folk knew their business; cyclists often arrive like we did, starved, tired, wet, and no questions are asked – requirements are known. There was a fire in the front room, deep armchairs, books, and from the blackened roof-beams huge bacons were swinging, the table was very old and heavy, and on one snug end of it a festive supper was laid. Various food and good, with strong coffee to stimulate yawning reaction; the food was home produce or stored for this very night – for us, we felt. The dalesfolk make you feel like that.

With half an hour to midnight we went to bed. Up above, on Buttertubs, the nor’easter was driving sleet into the drift. A grey mist possessed the wilds; the tracks of a single farm cart lumbered over the pass……… maybe now they were buried under the new snow. At the undefined roadside slender cornices of snow hung over silent pits to launch the wandering sheep into oblivion. We went to sleep………

The bedroom window abutted over the road. Fields of wearied green beyond, and moorland fellsides hugging them within narrow limits; the sky was grey and cold like the mist had been last night, and the nor’easter was still blowing, not so hard, perhaps, but the wind was only resting and in a few hours would renew his power – perhaps with rain or snow – or sleet. February was here now. Yesterday had still been the first month of the year, but today was a definite stride ahead. Old people and weaklings dread the month, for February kills, but Spring is cradled too, and lower in the dales the snowdrop – the crocus too if the month is kindly – will push through the winter earth. There was a stride forward in that grey Sunday morning, for February had entered the dales.

The ‘Cathole’ did us well. Breakfast was the result of years of close study as to the basic needs of cyclists about to cross Tan Hill. Not that Tan Hill is such a terror to face; it is hard – any mountain crossing must be hard, and it is long, but we knew that deep snow lay on the way – untrodden, maybe, and the breakfast fare laid for our assimilation was calculated to help us, to fortify us. The threat in the sky came to pass at that breakfast table; rain settled down, and capes and sou’westers came out. We faced the mountains again after the merest introduction to the infant Swale, bawling along on its deep-set course down to gentler meads.

Progress at first was not severe, for after the stony road had taken one leap out of Swaledale head, it settled down to a gentle tilt along a moorland depression – Stonesdale – to the snowline. The snowline was definite; one minute the road was clear, the rest we floundered across a drift, and thereafter the Cathole breakfast proved its worth. There are some old ruins at Ladgill; we missed the road and found the ruins, for no friendly cart tracks, not even single footsteps, had left their marks on virgin snow. We found a ditch too, with a stream underneath, and the water was cold to the feet. The road regained, our pace settled down to a long slog, with many a stop to scrape the stuffed snow from between the mudguards and the wheel, or to debate which was road in the unbroken expanse of white. The rain ceased. Then ahead a black speck showing against the snowy folds of moorland resolved itself into Tan Hill Inn, the highest in England (1,732ft) and we reached the fork road just beside it. From this point we anticipated a long series of swoops to the Vale of Eden, but the snow was the best scotch of the day. Riding was a farce, unless it was done for fun down the steeper parts, for heavy drifts across the road always concluded in a hectic skid. Snow is soft; often it received us hands first in wild dives, but it is never conducive to speed unless skis are used. We didn’t carry skis, but shall do so next time! A wild descent round an elbow called Taylor Rigg placed us in lower, clearer climes, but the road wriggled uphill again almost to its original altitude. Views were blotted by the grey mist that hung two hundred yards ahead, waiting for night to call it nearer. Just above Barras the road became visible underneath a thinner coating, and we slipped down to freedom in an exhilarating glide. Kirkby Stephen at 2.30pm, five hours, 14 miles. We thought we had done well !

We had lunch in Kirkby Stephen, and changed our stockings, our only contribution to a dryer existence, for the rest of our clothing would have to ‘dry’ on. At half past three we toiled up the long climb on the Sedbergh road. After that we drifted; the nor’easter had regained its old power, but now pushed us from dead behind; the road was all falling down a winding stream-fed dale with billowy fells bright with snow-tops, couchant on each side. It was beautiful. At Cautley the spectacular waterfall, Cautley Spout, lying back in a ravine, was a glassy line of spate, then we drifted through Sedburgh, and sat back waiting, it seemed, for village after village to be ‘lapped’ back, and for familiar scenes as lovely as ever to unroll themselves and roll up again behind till we came again. The final stage of Lunesdale was by lamplight, we climbed up through Lancaster to tea at Scotforth. Contrast? Morning miles; 14 in five hours: afternoon; 43 in two and a half hours !

The going continued good, and Preston receded to Walton-le-Dale. At Bamber Bridge Fred forked off for his Wigan; I endured many thousands of setts towards Bolton in company with a Manchester lad who was ‘all out’. The kind of fellow who rides a ‘stripped’ machine and gears up to 85. He had done Blackpool the previous afternoon in half the time we had crossed the hills from Newby Head to Keld. I crawled with him for many miles enduring his talk of a speed he could not then even strive for, and at length, as my way turned from his, I decided that he would never see the Dales by his own power. Blackpool, perhaps, but………………….