Post: This entry, as you will find out, is very long, and only covers the first day of a weekend. Charlie is instantly smitten by the daughter of Mrs Jones’s Bed and Breakfast ‘digs’ in Ffestiniog, a girl who he thinks is called Jean, but who turned out to be called Jenny. He makes many visits to this address and I would particularly recommend you read the Chapter on Page 159 of Volume 3 – but only after you have read ‘How the Year Began’ on Page 6 of the same Volume.

Saturday, October 31 Capel Curig

Tom and I had arranged for a weekend to Alum Pothole in Yorkshire, but last week, a workshop promotion made it impossible for Tom to ‘pinch’ a Saturday morning, and I, having got the weekend fixed in my head, decided to go alone – but not of course to the Yorkshire destination. Then I remembered a New Year holiday tour with Capel Curig as the centre, which has been projected for quite some time, and so I decided to visit the prospective ‘digs’ and see about it – alone.

It was a misty, heavy morning when I started just before 8am, and I made a dash out of Lancashire via Leigh, Winwick and Warrington. On Chester road it started to rain, and my cape came into active commission. I stood in Chester at 10.45am, wondering which way to go. Should I go via Holywell and St Asaph, and then shape my course owing to inclination either down the Conway Valley or over Nant Ffrancon, or should I go to Llandegla, and then decide the route? After some wavering I joined Wrexham road, for Llandegla, for it offered a better choice. If I did not feel up to much I could easily go on to Corwen and then take the Holyhead road to my destination, if that were not enough – well, down Nant-y-Garth to Ruthin and over the moors would make a good alternative – or Corwen to Bala and then to Cerrigydrudion and the Holyhead road again – and should I prove to be in hill climbing form I could achieve a long thought of ‘stunt’ by seeing for myself whether the Bala-Ffestiniog-Dolwyddelan roads were really terrors for hills and surfaces. Keeping my cape on continually through Pulford to Rossett, the Vale of Gresford, Cefn-y-Bedd – and that uphill tramp to the Nant-y-Ffrith turn. In the little glen at the foot of the headlong descent, I found a little wonderland of autumn colours, and in the sunken lanes that followed too. I put my cape away at Bwlchgwyn and hummed across the moors and into the valley to the Crown Hotel, Llandegla for lunch, with a four and a half hour run for a mileage of 56 prior to lunch. So far, so good.

When I was ready for the road again, the rain was driving down, and a heavy white blanket overhung the Maes-y-Chain. At the four cross roads at Dafarn Dywarch, I pondered for a moment. Should I go over the Horseshoe Pass and traverse that glorious stretch of Dee through Berwyn, or see for myself the autumnal splendour of Nant-y-Garth, or re-traverse the road direct to Corwen as last July? There was a problem for me, and it was only after some deliberation that I decided on the Corwen road – a decision that probably changed my ride into a renascence of wonder indeed. The road was dirty, but every bit as fast as last July, and my cape was put away at Bryn Eglwys, and the clouds, lifting from the blunt hills around, revealed a wealth of moorland beauty. Then the sun came out, and one by one, the peaks around Bala appeared. The Holyhead road – the road to Ireland. Yes, I would go to Bala, and by the best way – the hilliest way – the roughest way – but the way through the ‘sweet Vale of Edeymion’. So I turned to Corwen, crossing the swollen River Dee, and turning uphill.

At once my choice was justified, the wood and rock intermingled, the sparkling cataracts, the dirty, rough winding lanes – and I knew, that once again, I had recaptured the glamour that draws me irresistibly to Wales. Again the road was fast and I thanked the happy thought that put me on freewheel, for I could travel quickly and yet see so much. Beyond Llandrillo, I stopped to pack away my waistcoat and curse the folly of a sports coat in place of an alpaca on a hot day, and incidentally to look back down the valley towards Corwen, and enjoy the exquisite shades and the simmering woods and rivers and moorlands, and thought, as I invariably do amid such scenes as this, of those grinding away in towns or seeking artificial enjoyment in dance halls or theatres – if they could just be with me now, surely they would see the difference between their shallow amusements and the broad freedom that a bicycle gives them. Crossing the river at Llandderfel, I passed along the Vale of Penllyn to Llanfor and Bala. It must be market day on Saturday, for High Street was crowded with people who stared at my dirty machine and shoes. I was delighted – and surprised to see that it was only 3.30pm – I had two more hours of daylight, and so at once decided to try the wild Ffestiniog road, a road that is boosted by ‘Wayfarer’.

The road ran by the railway and the River Tryweryn – a boulder strewn waterway which abounds in pretty little cascades; in a little valley that was often picturesque, but more often spoiled with ugly hamlets and factories. The gradient was a gradual climb to Fron Goch, where the Cerrigy-drudion road went off to breast a high moorland ridge, whilst my road got steeper and improved scenically with the disappearance of the industrial vandalism. Looking behind I got a good view down the valley to the Berwyns, which were ablaze with autumn colour, and the sharp knife-like peak of Aran Fawddwy, of Bwlch-y-Groes memory. Higher and higher I climbed, the valley giving way to a shallow sweep in the moors, which became wilder and more desolate with every yard.

Afon Tryweryn was a listless swamp now, the bank of trees on the right dropped away before the flinty moors, the road was rough and grass grown in places, an isolated farmhouse of grey stone and many sheep which invaded the road were the only signs of life. Across the shallow basin rose a mighty mass of earth and rock, full of deep crevices and ragged peaks, lofty, isolated from the moors – Arenig Fawr, a mountain that in its position seems to me to be more impressive even then Snowdon. I could not help but stare and wonder at it, even as old George Borrow did in the 1850’s; he said that Arenig Fawr impressed him more than any other mountain in Wales had done – I would not say that, for Trifan holds pride of place with me as the most remarkable Welsh mountain. The moors here knew little autumn colour, for they are heather and bog and rock, grim and dark, but, oh, how fine! At Capel Celyn, the tiniest of hamlets with a general store, I managed to procure cigarettes; they only had Woodbines in but – I like the ‘evil-smelling Woodbine’ really. The hard road got harder, and I passed the little Inn at Rhyd-y-Fen, which Wayfarer finds so good, and at which George Borrow quaffed a tankard – a lonely place it is too! Still climbing mostly, with the scenery getting wilder, lonelier and Arenig showing his great form to still greater advantage, I had to open gates, and the road surface changed to loose, blue, slate-shale.

Then I heard a distant roar, coming nearer, and instinctively looked down the green track that passes little Llyn Tryweryn and runs into the gap of Cwm Prysor, remembering for the first time that a railway traverses this moorland col. An engine and train of wagons appeared, the metallic click of the wheels on the steel rails changing to a deep, prolonged booming which reverberated strangely across the vast solitudes. The train seemed a tiny, infinitesimal thing as it ran along the foot of the high slopes – the lower acres of Arenig. I turned again, for daylight was waning and I must reach Ffestiniog ere dark. Climbing a ridge past where a weather-grizzled old shepherd was driving a flock of sheep towards a lonely group of farmhouses, I swept down to cross a moorland stream and climbed spasmodically, the gradient bringing me out of the saddle. When the summit was reached at a height of 1,507 ft, I thought that I had come in the hardest direction, for I discovered that I had been climbing for eleven miles. But in front had appeared a range of mountain peaks, sharp, abrupt, rugged – a view that kept my eyes fascinated despite the bumping and crashing that my bicycle endured through neglect of the road surface.

The gradient was with me now, and I sped along while the coming night hushed the moors to a brooding quietness and the wilderness around became lonelier – stranger. Pont-ar-afon-Gam, where this neglected road is joined by another one, old, grass-grown, where a lone signpost, bent and scarcely readable points to Penmachno, where is an old farmhouse with a notice that says ‘Cyclists Teas’, where is a tumbledown bridge beneath which a swollen stream rushes. Pont-ar-afon-Gam. Here I left my bike for a moment to find Rhaiadr Cwm ‘The Cataract in the Hollow’, but failed to locate it. A little farther where the road runs on a shelf with a sheer drop of 50 ft over the wall, I caught a glimpse of Rhaiadr Cwm, the most magnificent falls I have yet seen in Wales. The Afon Gam descends a deep gorge, a rift in the precipice, which is so sheer as to be unapproachable, in several huge leaps. The swollen river was the whole width of the cleft, making the view of the foaming torrent extremely vivid. From the road summit another, different view fell to my lot – a view which I could never hope to explain, even with a pen like Basil Barham.

At my feet was the beautiful Vale of Ffestiniog, with the winding River Dwyryd like a stream of molten silver stretching along to the sea. The fading day threw a glamorous mist over the Vale – not a mist, a haze, the sky seaward retained a last bright streak, reflecting in the sea. On each side of the green and gold valley, reached a line of peaks, saw-like in contour, black, impressive, one that might make anyone stood there, and seeing them as I did, say with Borrow,

‘Wild Wales’.

I knew every peak – I named them from south to north, there was Llechog, above Barmouth, above the incomparable Mawdach, Diffwys and Y LLethr, the Rhinogs with Bwlch Drws Ardudwy between, and many lesser heights on one side, Moelwyn Bach overshadowing Ffestiniog. Moelwyn, that remarkable peak, which from this position looks as though the top has been sliced clean off, a range of lesser peaks again, behind which stood the splendid profile of Cynicht.

But here I was, with darkness creeping down and the road hardly discernible beneath me, and Ffestiniog yet three miles away – three miles below though! My freewheel worked overtime on that descent to Ffestiniog – and so did my one and only brake, so that soon I stood in the main street at the fork roads; the place was lit up by street lamps, under one of which I stopped to peruse the CTC handbook. I soon found no. 4, Sun Street (Mrs Jones) and the door was answered by a remarkably pretty girl. Here I was made heartily welcome, and sat chatting by the fire with (of all people) a Wesleyan minister, a very nice gentleman, Mr Rothwell by name, whilst Mrs Jones and Jean, [To sort out any future confusion, Jean was actually Jenny, but as I learnt many years later when I was researching the family of Mrs Jones, the Welsh pronunciation of Jenny sounds like Jean. It becomes obvious by reference to Charlie’s books that Charlie was very smitten by Jenny. Ed] got the tea ready and Jean went for some fruit and cream and cakes. A good tea, and ten minutes before the fire talking with Mrs Jones (and Jean) – Jean gave me a guide to Ffestiniog afterwards; I was almost persuaded to stay the night in Ffestiniog, but got away with the plea that it was too far from home (only 100 miles). At any rate it would have meant a lump of the same road over again. They were incredulous to think that I was going over the mountains to Bettws-y-coed that night, though I could not see why, though I did change over to fixed before I started, for one brake is often insufficient in these parts.

Ffestiniog gave me an excellent impression, firstly the Rhaiadr Cwm, then the view of its Vale, then its hospitality, and lastly, but not least, its pretty lasses! That reminds me of the verse that ends:

‘But fairer look, if truth be spoke,

The maids of County Merion!’

I don’t think it will be many moons before I visit this place again. Brilliant moonlight – as anticipated, it was a full moon, and perhaps the clearest moon of the year, for with the disappearance of summer, the heat-haze also goes, giving way to a clearer atmosphere. My little ‘two bob Lucas’ was of little use, for even in shadow, it gives but a pale yellow glimmer. Had the night been wet or cloudy, the crossing to Dolwyddelan would have been an adventure – and there was no alternative. But all was well.

Pausing a moment where the Bala-Maentwrog-Blaenau roads diverge, to ascertain my way, I soon left the quiet little town behind, and sped along a road that was overshadowed by great bulky forms, where sharp summits stood out clearly against the starry sky. The great hills on the right shut out the moonlight, and screened a greater part of the valley on the left. In front, the lights of Blaenau Ffestiniog appeared, then soon the scenery changed – a blight, so to speak, fell on the land. A tinkling rivulet hurried beneath the road, I looked for the shadowy trees, the green grass – the boulders covered with clinging moss, but saw, instead, a hideous mass of shale which formed the banks of a stream which stank and appeared discoloured. I hurried on, past huge slate tips to a town that, in its industrial meanness, reminded me of some Lancashire towns.

A long straggling place it was, with the houses on the right sometimes built directly beneath an overhanging cliff, sometimes below a shale slope, sometimes overshadowed by large factories. The town became noisy and well-lit and crowded with people. I pushed my way through the jostling mass, then the streets became quieter, and all at once I found myself above another noisy stream with banks lined with tall dark trees – and I rejoiced that Blaenau Ffestiniog was behind, but not the ugliness caused by it.

The road started to climb steeply, I left the trees behind and dismounted, walking between high steep slopes of broken slate: the moon shone on one side, revealing the true nature of the pass with cold, searching brilliance that I almost resented. The walk got harder, phew! it was a warm night. When the slope petered out on the left, it revealed huge mountains behind, the whole of which were scarred and broken – the whole mountainsides were vast quarries. Higher I climbed, until the road shook itself clear of encumbrances and left all traces of the chaos of Blaenau Ffestiniog behind. On the right a low ridge hid the view from me, on my left I looked across a little level where was Llyn Tfrydd-y-bwlch and a backing of rocky peaks all bathed in moonlight. A little farther on I reached the summit, 1,262 ft.

Then the descent of the pass down the side of, and round a shoulder of, Moel Farlwyd; sometimes the road in shadow, sometimes in moonlight, sometimes in long, easy sweeps down, sometimes in short, sharp pitches, round corners, one of which performed a complete turn about in so short a distance, and on such a gradient, that I had all my work cut out to get round at a speed not more that 6 miles an hour. Then the road went level again, I crossed the railway, and was in the Lledr Valley.

I stopped on Roman Bridge and stood watching the water foam down the glistening rocks, the Lledr dancing and sparkling in the rich moonlight, I rode slowly on the even, level road, enraptured with the autumn colouring of the woods and hills and the moon-toned grey and brown of the rock, and the liquid clearness of the hurrying river. I forgot the time – the day – the outside things – I had only eyes for what I saw and mind for what I might miss, no motors, no cyclists, no pedestrians were met; I had the Vale of Lledr to myself on that wonderful evening, I wanted it for myself. No amount of writing will describe it – no words could, and all I could say of it at every turn was “Magnificent, magnificent!”

Then on my left, on the summit of a huge rock, a square solid looking tower appeared, and I remembered that this was Castell Dolwyddelan. It seemed to be wonderfully in keeping with the rugged majesty of the surrounding mountains – indeed, it can almost be said to have grown with them, for this rude ruin has stood for almost 1,500 years. Here came Iowerth Drwyndun when he was refused the British throne because of his broken nose, here the great Cymryc hero, Llewellyn the Great was born, and here the peaceful Meredith ap Ivan sought a quiet retreat, who used to, as Southey says:

‘Linger gazing as the eve grew dim,

From Dolwyddelan’s tower’.

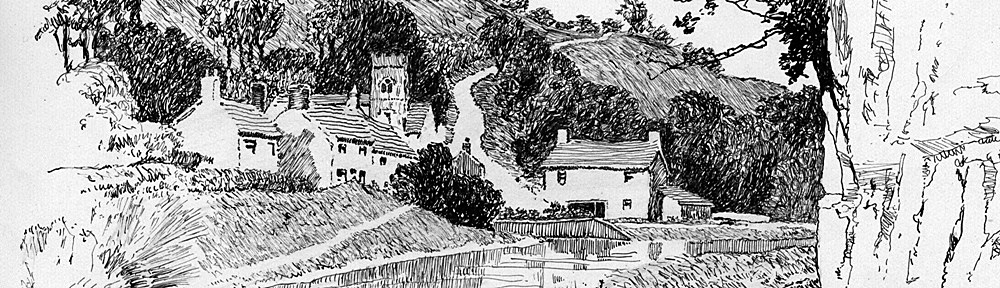

These things passed through my mind as I looked on the rough old edifice, and thought of the pageant of history that the precipitous crag it crowns has witnessed. Then on again by the multi-coloured banks on the left with its numerous little ravines down which some noisy stream would chatter, and the low meadow on the right, through which the river finds its course, and above which floated a low, white ground mist. I came to the tiny, ancient town of Dolwyddelan picturesque and in harmony in its isolation amid the greater isolation of the everlasting hills around it, a town I had never seen actually, but which seemed familiar, from the many pictures and paintings I have seen of it, Linnel and Varley, to name but two are great masters who have painted Dolwyddelan and its surroundings.

The hills on each side draw in again, the river keeps close companionship to the road and fills the air with its music. The trees overshadow the now rough road, throwing it in greater darkness. Here and there, a moonbeam comes through the foliage and make a pattern on the grey surface, which is strewn with fallen leaves that rustle beneath my wheels. A few cottages and a church melt away behind me, Pont-y-Pant. I make erratic progress, for I must keep looking over the wall to admire the river, or stop and look back at the wonder-pictures enhanced by the moonlight. Then I instinctively swerve across the river – another road seems to go on, and as I ride beside a high wall I wonder if I have gone wrong. The surroundings bear a strange familiarity which seems to grow on one, then I find myself on a smooth wide road, I cross and iron bridge and come upon a village – then I remember it all. The Holyhead road – the Waterloo Bridge – Bettws-y-coed! A clock in the village struck 8pm just as I stopped in Pont-y-Pair to watch the River Llugwy wildly and noisily fling itself beneath the creeper-clad and moss-grown arch.

Again all signs of life melt away behind me, for my journey is not yet at an end, another five or six miles must be covered. The road tilts upward, and I get down to it, increasing my pace from the eight miles an hour or so of the Lledr Valley to twelve miles per hour, for before I retire tonight I have much to see. For a little while I climb until a row of cottages appear on the left, I stop on the right, leaving the bike by the wall and carefully walk down a path, descend a few rough steps, spray splashed, and reach the narrow, stout, steeply ascending bridge known as Miners Bridge. From the middle I looked down over the handrail at a maelstrom of creamy water raging incessantly between smooth grey rock-walls. It was a weird sight in the moonlight, holding me fascinated with the wild torrent and the continuous steady roar. Then I slowly went back to the bike and remounted.

A large hotel appeared, and simultaneously I became aware of a deep roar coming from the woods on the right. Again I stop and leave the bike, going through a ‘penny in the slot’ turnstile, and going on rough, steeply sloping ground, I again reach some steps with a handrail to guide me, until the spray comes thick and wet, and I stand, a hypnotised witness of a terrific spectacle – Swallow Falls in spate.

The moonlight was thrown full on the madly rushing water, a sight that was a hundred miles of riding alone. From my position, I could hardly see the upper fall, but stood on a boulder at the foot of the second fall and just above the third. The water came leaping over the boulders and foamed and roared at my feet with such force that the air was filled with spray, descending on me like heavy rain, so that soon I was wet through. But not for the sake of a wetting would I abandon this scene, and I stood there for full ten minutes until my shoes ran water, watching the awe-inspiring fury of the waters of Llugwy. Then I moved to another vantage point, from where I got a better view of the upper fall, the most majestic and inspiring of the three. It looked to me just like a great picture, finer than a masterpiece, and the deep booming roar like sweet music.

It was with some reluctance that I left Rhaiadr-y-Wennol and passed through the turnstile to my bicycle again. The Valley of Llugwy opened out and became a littler barer as I came to Pont Cyfyng, where once more I peered over the walls to watch the river plunge wildly between great white-grey slabs of rock. Across were the row of cottages, in one of which I should find a haven for the night. But not just yet – no I must go up to the fork-roads at Capel Curig and see Snowdonia in the light of the moon, for I was loth to give my ride up yet, on such a night as this.

The valley was opening out now, was more bare, wilder, more desolate. The hillsides, which lower down were clothed in golden, glowing vegetation were here brown, sweeping moonlit moors, sometimes breaking into little crags, grey or black. There was Moel Siabod, dreary enough from this outlook, a long heaving waste of moors and marsh, culminating in a desolate peak, a striking contrast to the fine semicircle of precipice which is seen from the other side, or from Bettws-y-coed.

Ah, there was a change again, rocks, rocks, rocks, the houses appeared at Capel, the big hotel, then the joint roads. I looked on shining masses of rock, precipitous crags, soaring into the transparent sky…. Glyder Fach, I turned to see the greatest, the loftiest, but over the three peaks of Snowdon a billowy white cloud-bank hung, for all the world like a great snow-white silken curtain. Grib Goch, the northern tentacle of Snowdonia stood out of the snowy mist like a huge saw edge, Y Lliwedd was hardly cloaked, for the moonlight was directed full on the lower cliffs. I think that it was better to see Eryri as I saw it, for it gave an awe-inspiring effect. For the first time today, an overwhelming sense of loneliness came over me, the dead quietness of the night, the moonlit solitudes of the mud sides of Moel Siabod, the bare valley in front culminating in Snowdonia and its clinging blanket, the huge rock-masses of the Glyders, all dead quiet – vast, unworldly, in the moonlight.

At length I turned and sped down again to where the silence was broken by the vivacious Llugwy. I crossed Pont Cyfyng and stopped at the little cottage. “Could you put me up for the night, please?” “Yes, come in”, and I was welcomed into the warm kitchen. Mrs Jones busied herself about supper whilst I was being taught the intricacies of the Welsh language, a language that I have no hopes of ever being able to understand properly. Supper of sausages and meat, a chat with Mr Jones, then a walk outside, to savour the last cigarette of the day!

As I leaned over Pont Cyfyng smoking and watching the river pounding the grey rock just as it has done for thousands of years, and will do again, looking down the Valley towards Bettws, where the low white ground mist was rising, I reflected on the day and on the wonderland I had seen and felt truly thankful for the whim which irresistibly forced me to this weekend.

So to bed, to be lulled to sleep by the eternal roar of the Llugwy just below the window… 123 miles