Post: This is an interesting account of a day which includes a bit of everything, from severe (or even very severe) rough stuff to the Blue John Mine, famed all over for its bluestone products. And our heroes, and they were this day, managed all that on a discounted entrance fee. The would have looked shabby, being covered in Chee Dale mud.

Sunday, October 4 Chee Dale and the Blue John Mine

It all started because of a run in February this year. That day we had attempted to force a way through Chee Dale, along which runs a path – of sorts, but melting snows and heavy rains made the Dale impassable, so we had to admit defeat, ignominious defeat by water that foamed between unclimbable cliffs, and made, by way of some relief for our lowered colours, an eternal vow that Chee Dale had not done with us. And now, in October, we remembered our vow and arranged for another attempt on the limestone gorge whilst the river was low, for when winter comes there is little hope of getting around the rock barrier for months on end. Kingsway End, 7.30am we must meet, early as usual, but there are other attractions besides Chee Dale.

The clocks had to be put back on Saturday night, I got up at a quarter to four, had my breakfast, then discovered that it was only 2.45am! Anyway, I stopped up, and before 6am was on the road in daylight. There was no sunrise to be seen, a clammy mist shrouded the land, hiding the industrial and suburban outlook effectively. I got there first, and when Tom came we fell to trying to work out the way which cuts the Stockport and Hazel Grove setts out, and brings one out on the climb for High Lane, a desirable direct way which saves two or three miles, but gets us in an awful muddle at Bramhall Green. Often in the past two years have we tried to find our way along this cross-word puzzle of lanes, but always at Bramhall Green we have failed, and though we have not given it up, we have started to use another way, longer, but far better than the Stockport setts! But now we decided to try the maze once more, for – once found, it would never be forgotten. We did famously at first, then somehow found ourselves at Cheadle Green – and knew that once more we had failed. So we resorted to the other road and so came to High Lane by a lane that heaved in mud.

A drag to Disley was followed by a decent run on a level road, the ‘shelf’ road by New Mills, which gives some excellent views Peakwards, today denied to us. From Whaley Bridge, the climb starts in earnest, onto the brown moors, and beneath which road lies the Dale of Goyt. As we got higher we climbed into the mist, until we reached the commencement of the Horseshoe at 1.300 ft, where we could barely see beyond the confines of the road. The Old Road took us down into the valley, then made us walk out again to the main road at the summit, 1,401 ft. A shiveringly cold run downhill brought us into Buxton, out of the mist. The shortest way out of this Fashion Parade is the best way out for us, and very soon we found ourselves running between limestone walls and the sewage works of spoiled Ashwood Dale.

We stopped at the gorge of Lover’s Leap, where we were surprised to see no water coming down the river. Last February this was a raging torrent, and even during the June heat wave a goodly amount of water was flowing. We walked between the dripping rock-slabs to the shelf over which some small amount of water was falling. How was it that none whatever was going into the Wye? Beyond the waterfall the gorge shallows into a pretty little dell. Then following the course of the water, we discovered that it was ‘swallowed’ in the middle of the ravine. The porosity of limestone accounts for this, but it will only take a certain amount, the rest overflowing down to the Wye. At least that is our version of it, and it sounds feasible.

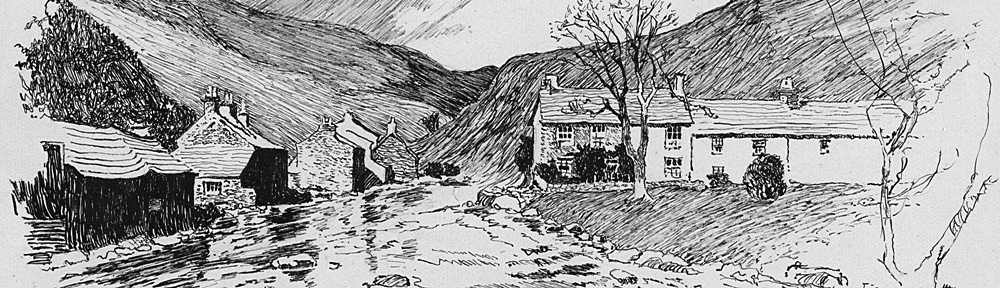

It came down to rain pretty heavily as we remounted and left the gas and sewage works behind, entering Wye Dale, where the river is released from its concrete bed and takes a more natural course. Quarries mar the effect somewhat of Wye Dale, whilst some of the lesser dales that converge from it have been turned, lock, stock and barrel, into industrial concerns. Just where the road tilts upwards to leave the Ravine and climb Topley Pike, we abandoned the main road, passing through a gate and entering on a pathway along which was strewn a generous amount of sharp, flinty stones. As it leads past a small works, it had probably been ‘repaired’ to allow carts an easier passage. This route was about a quarter mile long to the cottages at the commencement of Chee Dale, and as we rode it all with a reckless disregard of tyres, the wonder is that they came through unscathed. Crossing the river, we reached the buildings (in one of which we had our lunch last February), and from there Chee Dale – and the tussle – started. The limestone cliffs on each side were taller and more sheer here than hitherto, and the path narrowed down to a mere track. A youngster informed us that the stepping stones would probably be submerged, but we answered that we could swim!

One or two stiles, a rough crossing of broken rock and flinty outcrop brought us along to where the path was all water and mud, and to where we had finally been checked last time. The river was lower, and we perceived that though it ran flush with an overhanging mass of rock, stones had been placed along by the cliff to enable one to get round, so we shouldered our bikes and stepped out to the water. It was rough, too, for these stepping stones either came to a point or else rocked or where partly submerged, and to make matters worse, they were too near the cliff face. The rock, bulging outwards, caused us to bend down here, or lean outwards there, the while we poised artistically on some wobbling stone.

Halfway along was a little beach, on which we rested, sheltered from the rain. Oh, but the scenery was magnificent, the great rock bastions, the swirling river and the delicate colour that autumn had given to the woods. White and grey were the enclosing bastions, green and clear was the water, which leapt in many little cascades and rapids, and was turned a creamy white, brown and gold and green in a variety of shades decked the trees, and the ground plants, grass and undergrowth, nettle and bramble, put a finish to this pageant of nature.

We managed to get across the stepping stones alright, though, as a matter of course we got our feet rather waterlogged, but that is a regular Sunday happening, a thing which is liable to obtain even during a heat wave. In comparison with the route that followed, these stepping stones faded into insignificance. The general surface was composed of clay, set on a camber steep enough to make us slip continually into a morass, in which grew dense masses of nettles, and here and there we had to climb jagged little crags. For slipperiness, limestone takes some beating. The best way to get along – and by far the easiest, was by carrying the bikes all the time. A huge bastion of sheer rock towered in isolation across the river, Chee Tor, whilst looking back from where we had come, bulging cliffs overhung the stepping stones. Then the dale narrowed and the river flowed swiftly into a deep, silent pool, hemmed by an impassable precipice, on the edge and sides of which were stately trees, bent over, and:

‘Reflected in the tide the grey rocks stand

And trembling shadows throw;

And the fair trees lean over side by side,

And see themselves below.

A long narrow plank, half rotted crossed the stream, and as we trod warily across, we could feel it creak and give beneath our weight, then on the other side the path climbed to the top of the cliffs, so near the edge that a slip on the clay or rock would send us, bikes and all plunging over into the depths. Then it descended precipitously to the river again beyond the channel. Progress could only be made inch by inch with the utmost care. A stouter plank conveyed us back to the other side, where we came up against the hardest obstacle that it has ever been our privilege to overcome. We had to scale a 10 ft crag, and just on the top, a big tree had fallen across, two huge fork-branches just being placed in such a position that made it impossible to reach the summit with the bikes. To the right was a sheer descent to the river, and on the left, the rocks climbed to the roots of the tree which was like a wall. This was the only way possible. To make things more hazardous, beyond the tree was a steep slope of clay, upon which it was an impossibility to get a firm foothold – or so we thought. The slope ended on the edge of the cliff.

We explored roundabout for a while, then thought out the best plan. I hoisted the bike up from a little ledge, holding it as high as possible, whilst Tom leaned over the tree and managed to pull it to the other side. Now came a crucial moment. He left the tree and tried to cross the clay slope with it, but slowly he slid down the slope, despite vigorous efforts to keep a foothold. Things got desperate, meanwhile, I tried to get round the tree in time, struggling to get round the mass of roots. Just as he was nearing the edge, I got across the clay and made a grab at my machine, hoisting it to safety, and Tom, free now, soon regained firm ground. So much for one! Obviously that plan would not do again, so with a change of tactics, I got astride the tree, Tom lifted his bike over his head, I got it and pulled it to the other side, holding it whilst he regained the treacherous clay. Now he ‘dug himself in’ by his heels, and carefully drew his machine across.

Then I found that I could not get off the tree, and had to work my way backwards to where I could get a handhold. It had taken us half an hour to get two bikes over a tree trunk! Our clothing was full of clay: it showed in big yellow-brown patches all over my black alpaca, our sodden shoes were thick with it – but by gad it was worth it! The glistening grey cliffs and exquisite colouring and mingling of wood, rock and water were enough payment for us, and if not, why the very joy of dragging a bike through and over the obstacles of Chee Dale satisfied us. Then we had a long walk by the river, through mud and over crags, in the beautiful woods, carrying the bikes nearly all the time. Skirting a sinister looking morass, we crossed another deeply wooded dale, and stood wondering which way to take.

A gentleman and three ladies came up, and told us that by turning left we could soon reach a road, but we preferred to turn right and keep to the dale. They said that it was hard going, and that, like them, we were plucky to turn out on a day like this, to which we replied that we had seen nothing wrong with the day, it was wet, perhaps, but that was nothing extraordinary. After that progress was more or less easy, and soon we reached the road at Millers Dale. If they called that latter bit hard going, what would they say to the rest? At Millers Dale we found that the two and a half miles of Chee Dale had taken us over three hours, and recorded it as the hardest scramble with a bike we had ever had. We soon found a place for lunch, a cottage that did us well. Then the road again, the Tideswell road that leaves Millers Dale, but not before giving many entrancing glimpses of this Ravine. From the Cathedral of the Peak, we crossed the bare green moors which are so much dissected by white walls, then found ourselves running downhill into Bradwell Dale, another limestone gorge which, however, is devoid of trees.

At Bradwell we enquired of an old lady, of the possibility of getting into Bagshawe Cavern, an underground chain of caves and halls that is said to beat all the Castleton wonders into a frazzle, but were told that we should have to find the guide, so realising that this would cost more than we at the moment possessed, we decided to leave it over to a more suitable time, and so carried on to the main road at Hope, and so to Castleton. A thick mist was gathering which all but obliterated the ruined silhouette of Peveril Castle, and which shrouded the hills in front of us. We left the main road and made for the Winnats, past the entrance to Speedwell Cavern (of recent memory) but we did not see the pass until we were in it, so thick was the mist becoming.

As we climbed higher up the gorge, the pass became awesome. Seeing only the base and the rising, tottering crags, we could easily imagine ourselves somewhere in the dark clefts of the Caucasus or the fearsome charms of the Himalayas, an image that grew upon us as we scrambled hotly through the mist. On the summit we turned towards Mam Tor and flew down to the main road, halting where a blue flag hung dejectedly by the roadside, and where a notice in blue lettering extolled the superior virtues of the Blue John Mine, and invited us to behold the said virtues.

We fell for it, leaving our bikes by the inside wall and traversing a misty track to a stone hut that served as shop and paybox. We refused to pay £5 for a little ornament of the rare, beautiful fluorspar found herein, mostly because we hadn’t £5 between us in the world. Indeed, we hadn’t much more than 5/-. We were much impressed by a dismal-looking hole that yawned blackly in the rock, but when the young woman in charge wanted us to pay 4/6d for the privilege of becoming rabbits, we ‘kicked’. If we just paid that, where would our tea come from? Neither of us was blessed with undue wealth. She said that we had just missed a party, but when we showed signs of retreat, she offered to send us to catch them up for eighteen pence each, to which we concurred, and a lad came, gave us each a candle, and led us into the Stygian darkness.

It was a long, downhill, eerie journey; rough steps conveyed us down between dripping slabs of rock, we rounded corners at right angles, and crossed wooden planks from which came a shiveringly hollow sound. Although the passages were tortuous and narrow, they were very high – we rarely could see the roof. Sometimes thick white encrustations that glittered in the flickering candlelight, were seen, but our leader never stopped or spoke, except as a word of warning when some dangerous point was reached. We kept on going down, whilst we dwelt upon the fact that we should have them all to climb again – or else even more, presuming there was another way back. Just as I thought we should reach the nether regions, we heard voices below us, and saw a ghostly group of five round a powerful acetylene light. And so we joined the party.

Our guide was not one of the usual traditional, chanting kind; he was an intelligent talker, one who knew what he was talking about, he advanced theories, pulled others to pieces, invited questions and answered them in a convincing fashion. He had a horrible cough, strange to say, similar to the guide at Speedwell Cavern; perhaps it is one caused by these damp, heavy regions ‘down under’. About the cavern we were now in:

This is known as Lord Mulgrave’s Dining room, because he used it as a place of repast for the miners who accompanied him on his seven day’s exploration of the mine, in a vain endeavour to find another outlet. BBC radio has been received in this cavern, on one occasion a whole concert was listened to by an invited audience. Here have been left veins of the Blue John ore, to show its position and formation.

The guide gave us an interesting lecture on the method of mining it, with the attendant difficulties, then we moved off, by a winding, vaulted, pathway, passing innumerable clefts and cavities, the extent of some has never been discovered, though they have been traced for as far as three miles, to what is known as the Variegated or Crystallised Cavern. Here we were met with a gorgeous stalactite of varying colours reminding me of a fairy palace. One group of slender white columns, some of which a vandal has broken, is called the ‘Organ’ from a fancied resemblance to the latter. Then there was a crystallised waterfall – just like a waterfall that has entirely frozen over, and smooth as glass. All over the cavern, the walls were coated with this substance, whilst in some places glittering icicles hung or others rose from the ground to meet them. The formation of these stalactites and stalagmites is interesting enough to be recounted, as the guide told us.

They were formed by water charged with carbonic acid gas coming through the porous limestone; on reaching the cavern, the moisture becomes evaporated by the air, when the lime, previously held in solution, is deposited in a thin layer on the surface of the rock. Each succeeding drop leaves a fresh coating of solid matter, until in time these successive additions form an irregular, elongated cone resembling an icicle, called a stalactite. If the water flows too rapidly to allow of evaporation, it falls to the ground and in a similar manner forms a calcareous cone rising upwards. This is know as a stalagmite. Sometimes the stalactite above the stalagmite below keep increasing in length until they join together and form a column of delicate beauty. About one twentieth of an inch of a stalactite forms every 250 years.

The seemingly thousands of steps back to the outside world were made easy by the guide pointing different wonders to us as we ascended. Then came the ‘tipping’ – and if ever a guide earned a tip, it was ours.

The outside world was wrapped in misty gloom as we retraced our steps and reached the road again. Rain started to fall, and we rode inside capes along Rushup Edge. Breathlessly descending into Chapel-en-le-Frith, we rode rapidly along by Coombs Reservoir, for we had a mind to join the club at Bollington for tea, and our route was the reverse of flat. We crossed the Buxton road at Whaley Bridge, climbing into the mist again. If in a hurry, don’t traverse the Whaley Bridge to Macclesfield road. It just isn’t done! Half an hour’s tramp brought us to the summit, from where we swept into Kettleshulme, and started all over again. Then another fierce descent and another half hours walk up the Charleshead Pass, decided us as to the tea place.

Too late for Bollington, so Pott Shrigley would serve us; it was lighting up time now and the heavy mist further darkened the world. Nevertheless we rode lightless down the rough, beautiful road, rapidly unclimbing all that our perseverance had brought us to, and reaching the pretty village in a short time. A wash, and tea in a hut in the garden adjoining the old-world cottage – a modest tea, for funds were very low. We timed it nicely, 1/9d each. Tom was clean broke, having just enough, I had a one and a half pence left. The first time I have seen Tom so poor! Anyway, all’s well that ends well, and soon we were skipping lamp-lit along a maze of dark lanes to the Stockport road, leaving it at Poynton, and eventually coming to Cheadle on the same road as this morning. We parted here and I soon got over the 16 miles of suburbia and factories.

There have been a host of attractions on the plate for today, from a tough dale scramble to cave exploring, a phase which ‘grows by what it feeds on’ with us, and the countryside is at its best. Autumn Glory! 114 miles