Post: On this page you will read of Charlie and Ben’s ascent and crossing of the ‘Pass of the Cross’ or Bwlch-y-Groes. It is a fantastic pass and crossing, and is set down by Charlie in great detail. I first traversed it in 1956 with two gentlemen, H H Willis and a man who was to become later the Secretary of the Rough Stuff Fellowship, Fred Dunster. The occasion was the very first AGM of the RSF and a ringing endorsement for travelling on roads that were yet to be tarmaced.

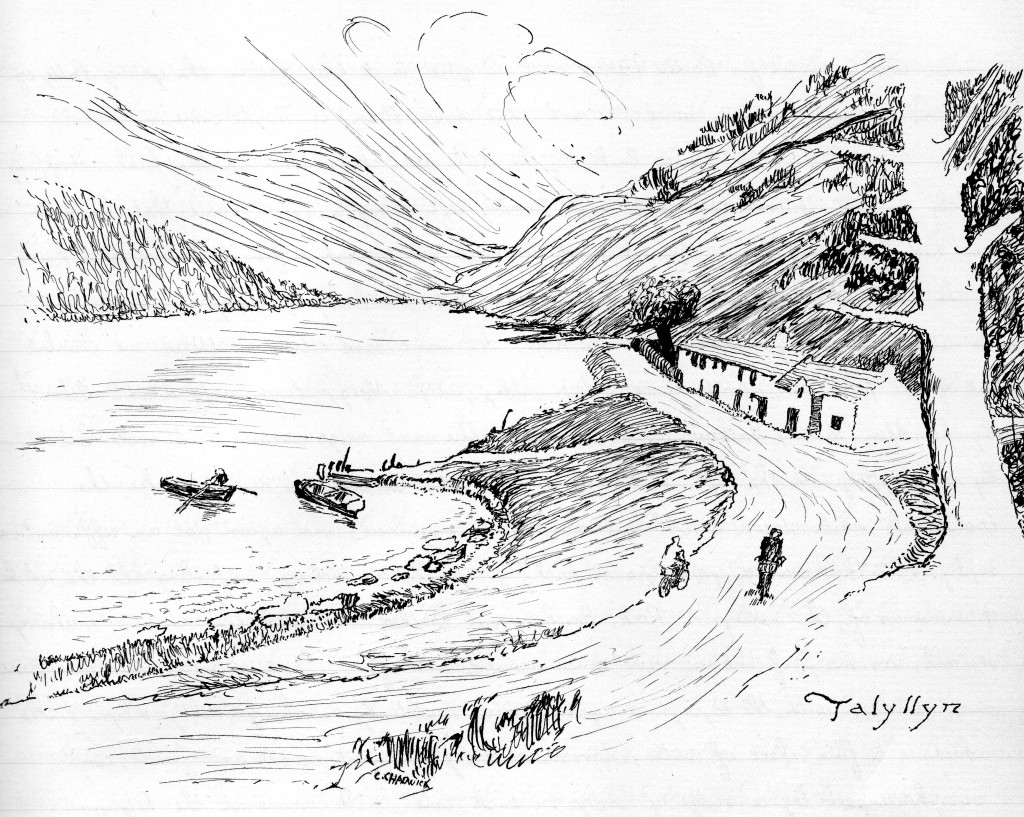

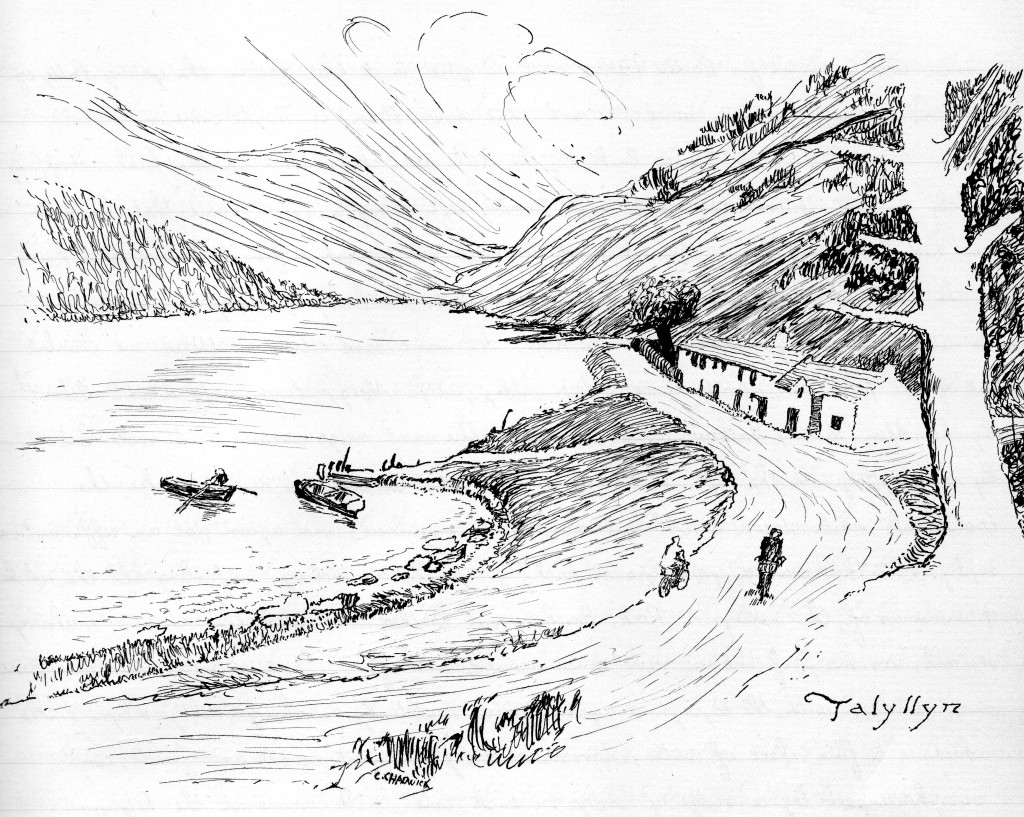

Thursday, July 2 Tal-y-Llyn to Bwlch-y-Groes

We were all up early this morning, Ben and I going out for a walk. In the street we met four more Boltonians, chatting for a short time, then going in to a fine breakfast. I had stayed here before in 1923, and as I expected, we found it very reasonable, paying 5/6d. It is to be recommended. It got very late – almost 10am before the five of us could get out on the road again, owing to the need for minor adjustments on the part of our friends. We crossed the bridge, joining the Barmouth road, and having a strong wind behind, made a fast pace. Rather too fast for the surroundings, I thought, yet as I was one who led, I can’t say anything! Unfortunately, the sky had assumed a different aspect this morning, one of dull heat, so that the mountains were mostly hidden from view, and there was no distance to admire. Still, the most befogged atmosphere could scarcely hide the wonders of this estuary road.

This panorama of panoramas is the Wonderland of Wales. As one draws near to Barmouth one begins to realise fully with how prodigal a hand – with what liberality – things of beauty and amazement and magic have been thrown down here. The shining river, the half glazed mountains, the trees, the restless sea beyond the bridge, the extensive coast line – the whole range of sights is stunning and overwhelming. We stopped just by the bridge in Barmouth (Memories!), and had a lengthy talk. They told us of the atrocious surface of both sides of the Tal-y-Llyn Pass, and asked of our intended route. We said that we had above half a mind to try two of ‘Wayfarers’ stunts, Bwlch Oerdras and Bwlch-y-Groes, and perhaps Milltir Cerig. They had only a hazy notion of the route, and as it was off my maps (having but the right one), I could hardly show them, so we let it go at that. About 10.15 we parted, for they were bound north and we south.

We then got extravagant, spending money with a reckless hand, for 2d each went on the bridge toll. It is worth 2d of anybody’s money if only for the wonderful views up river it affords. When I looked at the giant ridge of Cader Idris, I thought of these lines:

‘That rock where the storms heave their dwelling,

The birthplace of phantoms, the home of the cloud,

Around it for ever, deep music is swelling,

The voice of the mountain – wind, solemn and loud’.

Although not nearly so high as Snowdon (being only 2.927 ft, 633 ft lower), Cader Idris ranks second in majesty and finesse of outline, and possibly gives finer views than any of the Snowdonian group, the views to the east stretching right over Shropshire and Cheshire, northward to Snowdonia, westward to the Irish hinterland, and in the south down to the Brecon Beacons. It is a long railway bridge, Barmouth, the footpath running into deep, dry sands at the southern end. We must have gone wrong, for we found ourselves in the railway station (Barmouth Junction), and had to cross the line and get over a fence before we managed to reach the road at Fairbourne.

From here the road climbs uphill, giving a beautiful sea-view of a beautiful sea. The sun was warming up now, and every stream – as on Tuesday – was requisitioned to remove a constantly returning thirst. After the climb comes a gradual drop to Llwyngwril, which is pronounced by taking a deep breath, and with tongue against your upper teeth, rattle it out ‘Thlooingooril’. It is advisable to practise in a quiet spot first, otherwise objection might be taken, even then it is impossible to pronounce it as the natives do. Llw-etc is a very primitive village, and would make a nice little place for a quiet holiday. More fine coast views to Llangelynin, where we turned inland and caught the wind which blew against us in solid chunks. At Rhoslefain we obtained more water (which had become so scarce that we shouted ‘Alleluia’ when we discovered some), then ultimately came to Trychiad.

A road led towards the mountains whilst the main road ran round to Tywyn, and with a shrewd suspicion that this byway would cut out a number of dull miles, we enquired and as expected, found that we could get to Tal-y-llyn that way. So we went on our way rejoicing. Passing through another primitive village that used the road as a farmyard – Llanegryn – we approached the mountains, the scenery becoming more and more wooded, whilst in front on the right, was a huge bulging rock that overhung the road. At length we crossed the River Dysynni, and stood beneath the crag which is called Bird’s Rock, in Welsh, Craig-yr-Adeyryn. It towered overhead very impressively in huge bulges, and the innumerable cracks and ledges on it were alive with birds – it is a very appropriate name.

Gates appeared on the road, the surface was developing into a shambles, and little hills constantly got in the way. The Dysynni was crossed again at Pont Ystumaner, where we had the pick of four roads, the signpost (half wrecked) pointing straight on for Llanfihangel-y-pennant, left for Bodilan, right for Abergynolwyn, and behind us, Towyn. It was just here where the map I had lent would have proved a boon, but as it was we had to guess – and we decided to keep straight on. When we reached the top of the next climb I knew something was amiss, for mountains made a complete cul-de-sac in front. We swept downhill fiercely on a road that would have made the bed of a respectable mountain torrent. It ended altogether at the village of Llanfihangel-y-pennant, where was a Temperance Inn that seemed to be just the place to stop a growing hunger.

They did us well in the shape of eggs and jam and beautiful bread and butter and cakes for only one shilling, and they apologised for having nothing in! We asked if there was a way of any kind over to Tal-y-llyn, but were told that we should have to go back to the cross roads and turn for Abergynolwyn. Llanfihangel-y-pennant, we learned was a centre for climbing Cader Idris, and so quiet is it that besides the young lady of the Inn, we never saw a soul. Book that down Ben, it might come in handy!

We turned back by the little stone church and up the hill, dropping swiftly to Pont Ystumaner again, and turning left along a gated road that looked none too promising. After a short climb it ran through a fine little moorland pass on the slope of Moel Caer Berllan (1,233 ft), with the hurrying Dysynni below, and the steep side of Gamallt across the river. It was a rare tit-bit. When we climbed out of the pass, we stood above a deep valley, with Abergynolwyn mapped out below by the Afon (river) Fathew, and lines of gully-rent crags across. A road led by some cottages on the left, and with an idea that we did not need to take the breakneck route down to Abergynolwyn, we enquired and again got an affirmative reply.

This was a grass-grown path, gradually descending, unfurling all the while panoramas of the valleys. Rock, bracken and heather constituted this slope, making in all as magnificent a run as one could wish for. We entered a wooded part and came in with the Dysynni again, quite suddenly reaching Tal-y-llyn lake, which is a fine sheet of water, surrounded by pleasant woods and fields, and overshadowed by a ridge of crags on each side. I commend the Dysynni valley route as we took it, to anyone, as the best approach to Tal-y-llyn from the coast. And please not to forget Llanfihangel and the Temperance Hotel.Our road ran round the right bank of Tal-y-llyn, then struck across a flat green meadow.

Here we spoke to an elderly couple from London, who were staying at Aberystwyth, having a very interesting chat with them. They were wildly enthusiastic about the standard of scenery in Wales, but oh! it was so hard, walking! At Minffordd we joined the other road that comes down from Corris – a road that I knew, and immediately we found ourselves entering Tal-y-llyn Pass. Of course we were very soon walking, although the gradient was quite rideable; the heat was getting unbearable. Ben was feeling it, I yearned for water, every motor that passed threw up a cloud of dust, choking us, and making things generally unpleasant.

I minded that in 1923, two years earlier, I came over this pass on just another such day – a Thursday in the same Wakes Week, a day of boiling heat, dust-laden atmosphere and annoying motors. I also remembered a certain waterfall half-way along, and in the hope that there may be a drop left for us, we pushed on. Ah! there it was. Only a tiny trickle down the rocks, but as this is a very long, fine fall, in several leaps in wet weather, at the bottom of each leap is a deep rock-pool, and today these pools were full of clear, crystal-like water. We divested our shoes and stockings and jackets, and stood knee-deep in it whilst we had a good wash, submerging our heads in it and letting the sun dry us. About an hour was spent thus, until the merciless sun crept round and made us perspire freely as we stood there. The water even got warm. Had there been a little more water, I, at least, would have thrown all my clothing off, for we were secluded from the road here.

I put my jacket in the saddlebag – that is the advantage of an alpaca – before we started the long tramp to the summit. A view of Tal-y-llyn lake down the Pass was in part spoiled today by a heat-haze that persisted over the lowlands, but the opposite crags and gullies of Cader Idris were clear and sharp to the eye. After Llanberis and Nant Ffrancon, I think this ranks very highly for Welsh passes for rocky grandeur, and for a bad road surface, it is an easy first. The summit was reached at 938 ft (a rise almost from sea level), where is a small lake (almost dried up today) called Llyn Trograieryn, ‘The Lake of Three Pebbles’, (because of three boulders which stood near the edge). The descent which followed was through open green moors, wild, but except for a fine rock-group (Gau Craig on the western side), not very interesting. The road surface was the worst that we struck in the whole of Wales – and that is saying something.

Lower down we came by a stream and into a belt of woodlands, in which is situated the Cross Foxes Inn at the Dinas Mawddwy turning. We stopped, and I asked Ben if he felt up to another pass before tea, pointing to a white thread of road that curled laboriously up a distant hillside. “Certainly, carry on”, he said, and from those words we became introduced to two of the wildest passes imaginable. Just by Cross Foxes was another waterway which held enough to dismiss the persistent thirst for the nonce.

If we had forgotten the wind, we suddenly became aware of it now; it did its level best to stop us. Before long we gave it best and got down to shanks. All the time we were climbing into a region of wild green uplands, and behind us were magnificent views of the Cader Idris precipices. Bwlch Oerdrws! The summit revealed a country of huge green clods of earth with deep narrow valleys cutting in all directions into them. Charles Lamb once said “I don’t much care if I never see another mountain”. Can anyone stand on Bwlch Oerdrws and looking towards Dinas Mawddwy, repeat the words! I think not.

The name, Bwlch Oerdrws may be very apt, for even on a blazing day like this was, the wind was cooling. It would be the ‘Pass of the Cold Door’ indeed on a January day when the north-easterly gale was driving the sleet across the grassy green mountains. Ugh! A bus was coming up behind, and not wanting to get another dust bath, we started – keeping it behind. As one swoops downhill around many nasty corners into the valley of the Cerist, one realises the immensity of these lumps of earth. The cwms on the right are so deep and narrow that little sunlight can ever get to the streams below, whilst some points seem in perpetual shadow. For about three miles we swooped downhill, then the road in one place made a sharp twist to avoid a deep cwm. A byway kept straight on down into the dumps, and, curious, we followed it. It was a pretty spot spoiled by a dump of empty tins, ashes, etc. Crossing a footbridge, we climbed back to the road, and then entered Dinas Mawddwy.

The first consideration now of course, was tea, and again in luck’s way, we struck a peach of a place, ‘Brynmair’, opposite the Post Office. Tea, eggs, fruit (pears), and bread and butter, and cake, for 1/3d. Ben, it goes better! Dinas Mawddwy is set amidst beautiful surroundings in the narrow, deep valley of the Dovey; here an infant river.

‘Heddycol ddyffryn tlws’

Which George Borrow, who was enamoured of the valley, translated to ‘Peaceful, pretty vale’.

One thing that was very conspicuous from the Bwlch Oerdrws road was a mansion, the roof and inside of which has been entirely burned out, leaving just the bare walls. It is situated in the centre of the little town. A signpost says: ‘To Bala, 28 miles. To Bala, 18 miles. Motorists are advised to take the longer route, as the short one via Bwlch-y-Groes is unsafe’. The short one was ours.

As soon as we left Dinas, we found ourselves on a beautiful winding, hilly road which very soon brought us to Aber Cowarch, where Borrow, on discovering that this was the place where Ellis Wyn composed his immortal ‘Sleeping Bard’, in his own words “Sprung half a yard into the air”. “No wonder the ‘Sleeping Bard’ is a wild and wondrous work, seeing that it was composed amidst the wild and wonderful scenes I here behold”, he ended. We thought so too!

The valley got deeper and narrower and more beautiful at every mile, whilst we, high spirited with the type of country, composed words to fit popular music, sang snatches of Cumraeg verse, and sang such songs as fitted in with the land we were passing through:

‘My heart is in the mountains,

In the mountains, in the mountains;

My heart is in the mountains

My cycle as well!’

I am sure that if anyone heard us they must have thought us a trifle silly! Llanymawddwy! That reminded me of those fierce, bloodthirsty hillmen who one time roamed these hills, putting fear into the hearts of travellers and natives too, and were called ‘The Red Robbers of Mawddwy’. The one and only shop was closed (I was after cigarettes), so we had to carry on, I with a fear that I should soon be cigarette-less until morning, a gloomy outlook, a calamity indeed! Ah! the valley was narrower, the green hills steeper, hemming us in, then running through a wood, we got our first sight of Bwlch-y-Groes.

For three years I have read, marked, learned and inwardly digested anything pertaining to this region. ‘Wayfarer’ has exhorted all and sundry to see it, guide books speak of it in awed terms, road books warn people of the rashness in taking four wheels over, contour books show a gigantic hump and tell cyclists not to ride over it after dark, even signposts denounce it as unsafe, all adding to a growing wish to go over it – and now, here we are, on the threshold of this ‘Pass of the Cross’. And if I expected something uncommon, I got more than I expected.

At Aber Rhiwlech, where a deep, rocky nant bites into the craggy hillside on the left, behind which is a rugged peak showing to fine effect, the road gives a sudden, sickening lurch upwards, immediately skewing completely round at a gradient of about 1 in 5 and a half. “Death trap No. 1”, I said (for anything coming down), and we started. The road was rough and very narrow, the gradient easing off after the first bend, to about 1 in 9 – dangerous even at that. Across lay a line of steep precipice, at the end of which was a black, gloomy chasm, down which the Dyfi (Dovey) came. The road is cut on a shelf out of the side of the hill, sometimes being overhung by crags of various forms, whilst on the outside edge there is often no protection, nothing to stay the unwary traveller from going over the edge and exploring the foot of the steep slope unwillingly.

Over the edge of the cliffs across, could be seen a very thin streak of dampness, that would make a fine single-leap waterfall of at least 200 ft in wet weather. After some climbing of the gradient quoted above, the road again tilted upwards at a fiercer gradient than ever, climbing over a thousand feet in less than a mile, turning nasty bends and cambering towards the precipitous edge. Here and there was a gate across the road. As we sweated slowly uphill, with the road high (but not far) above us, we saw a whirl of dust sweeping round the bend on the road, and go fluttering across the ravine, to be followed by yet another. The light was beginning to deteriorate too – it was only about 7.30pm, whilst looking back towards Dinas Mawddwy, expecting to get a fine view, we were rewarded with a distant view of misty rounded summits, one or two craggy peaks, the glen of the Dyfi below, and a mass of black clouds overhanging all, a wild, sombre, desolate picture that was little relieved by the tree-clad vale below. The puffs of dust beyond the bend, the brooding sky, foretold a coming storm – and our jackets were replaced (the first time since Tal-y-llyn), though one might as well be without as with mine, an alpaca.

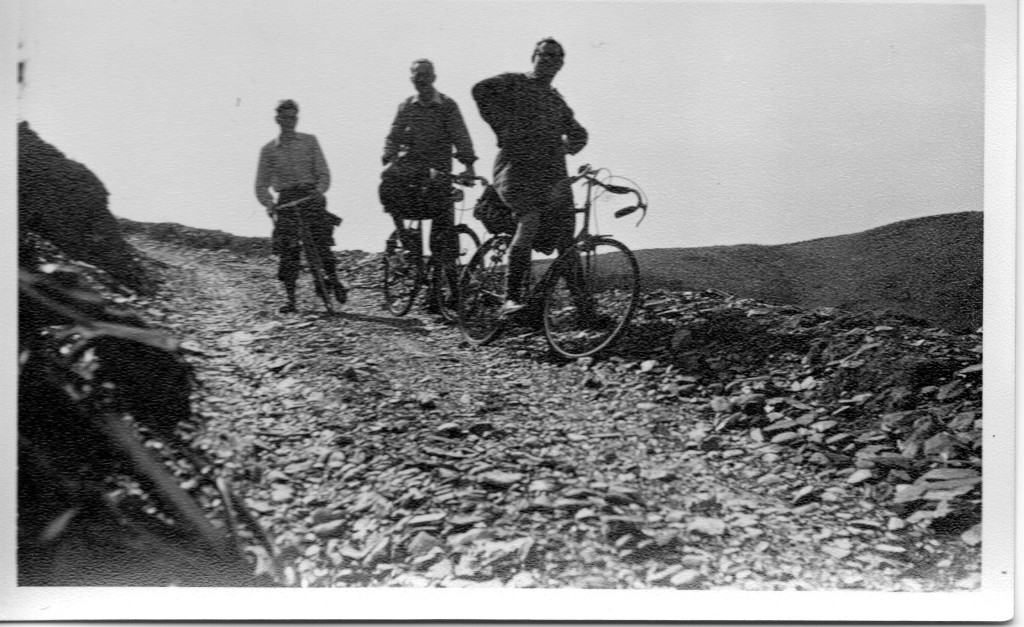

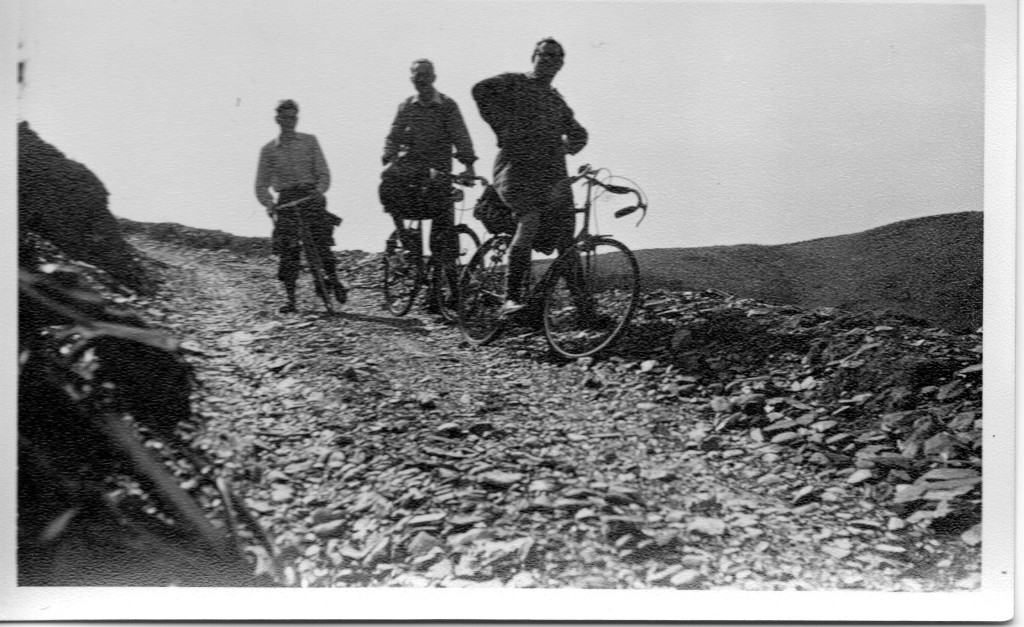

A figure appeared, coming towards us downhill, and as he stopped we asked him how much further to the top. He was a tramp to judge from his clothing and talked as if he was a professional one too, though he never tried to beg from us, and was quite nice, though once or twice I thought he was slightly ‘off his rocker’. It was an excuse for a stop. Once more we sweated uphill, with the atmosphere stiflingly close, and a heavy pall hanging over us. Then we heard distant, rolling thunder, the sky got blacker and blacker, whilst I, knowing the properties of Welsh rain on shelter-less moors, opened my bag and put my cape within easy reach. Turning a bend, the road ran more level, and another road – of sorts – a narrow, grass-grown track led away to the right; beside it was a notice, ‘To Lake Vyrnwy’, and in big unmistakable print ‘Impractical for Motors’. It is bad enough with a bike, and apparently steeper than Bwlch-y-Groes. The photograph below, taken by me in 1956, during a crossing of Bwlch-y-Groes, shows clearly the surface, probably little changed from 1925. The gentleman at the front, Vic Ginger, followed by H H Willis and a very good friend of mine John Barrow, were all attending the RSF Inaugural meet at Easter 1956. Ed]

A moment later we reached the summit of the Pass of the Cross, the highest carriage road in Wales, 1,790 ft above the sea at Tywyn. Gad, wild! Bare swelling moors, a rocky peak, a white ribbon of road that followed the contour, not a building, not a soul, a heaving black sky that seemed very near, and distant thunder which found a rolling, reverberating echo in every peak, and shook the ground beneath us. I prayed for a real storm, I was willing to get wet through for the experience of thunder and lightening at this altitude, I was willing to take what risk there might be, but after a few large drops of rain, the sky brightened up a little. The heat had gone, and though the wind had dropped to a breeze, we shivered with the chill.

We restarted carefully, for the road was rough, the gradient was not very steep however, and we were able to look around at the wide bare moors and rocky outcrops, and a deep valley that was just opening out on our left. Views, there were none, though for what I hear there is a mighty fine view to be had from the summit; George Borrow, who came over in about 1850 stated that he had a fine view of the Lake and Vale of Bala, the lake looking like an immense sheet of steel. We were unfortunate in the weather in this respect. About a mile further down, the road turned and ran across a precipice.

We stopped. Above, on the right, the cliff towered fifty feet or more, on the left we looked down into the valley. There was no protection, the road simply crumbled over the edge and dropped perfectly sheer into the valley. What an adventure in a mist! Farther down a gate appeared, then the two or three houses of Ty-nant, and we came along a sunken, winding lane, with the high banks ablaze with flowers, and the still, close atmosphere heavy with their scent. The view opened out later from the edge of Bala lake to an extraordinary jumble of mountains terminating in the rocky Cader ridge to the west, and the fine rock peak of Rhobell Fawr, and the sharp hump of Arenig farther north.

Some time later we reached the shore of Bala Lake, keeping to the south side. It is the largest sheet of water that Ben has seen – and is the largest natural lake in Wales, being eleven miles in circumference. (Lake Vyrnwy, the property of Liverpool Corporation Waterworks is the largest, but is artificial). Flies again were in much evidence, and once more my eyes suffered. With grand sunset views over the Arenigs, we reached Bala Bridge, where is a fine full-length view of the lake (Llyn Tegid), then entered Bala, just in time to get some cigarettes (9.20pm). We had a confab as to whether we should carry on or not, and scanned the CTC handbook but as there was nothing short of Cynwyd, ten miles away, we decided to pack up, and repaired to the Bull Bach where I had been before, receiving an immediate welcome. We met a couple of motorists (man and fiancée) who were on holiday. He was a humorist of the first water, a fine, interesting talker, and so was his girl. Of course we had the usual red rear light argument, but no malice was shown, and we got on together fine. We talked on many subjects from hills to Socialism – I learned that he was a Labour Agent for the Middlewich Parliamentary Division of Cheshire. I told them of Llanberis Pass and Nant Ffrancon and Idwal and Twll Ddu – and then I heard that she had been brought up at Bethesda! I shut up then! It was well after 11pm when we ‘chucked the guff’ and went to bed – the last night away on our wonderful little tourlet, dreaming of the Mawddach, Tal-y-llyn, Cold Door Pass and the latest thrill, Bwlch-y-Groes. 60 miles